'This fire is not over for us': 3 years after the Greenwood Fire

The remote village of Isabella endured the brunt of the 2021 Greenwood Fire, leaving behind a burned landscape, piles of waste, and lots of questions.

When a series of small thunderstorms skirted the treetops of the southern underbelly of Superior National Forest in August 2021, it was a welcome relief in that summer of drought. Unfortunately, little rain fell. But there was lightning.

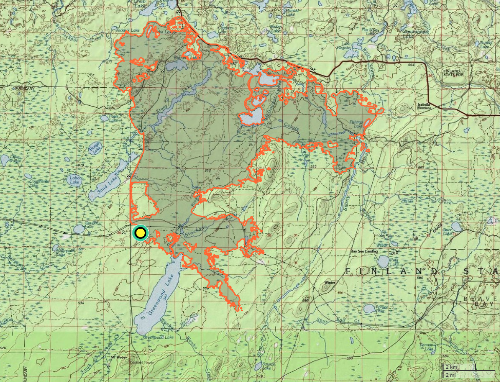

The Greenwood Fire, just south of Isabella, was made official the next day, on August 15.

A week later, more than 400 firefighters were trying to control a wildfire that one incident commander told the New York Times was moving like a “freight train.” The Greenwood Fire burned into December, even after the arrival of snowy, cold weather, months after it was officially contained.

A dozen cabins and dozens of outbuildings were destroyed by that time, and some 42 square miles were left black and charred.

Nearly three years later, people living in and around the Greenwood Fire are still deeply affected, trying to understand what a new normal looks and feels like in a burned-over moonscape. For others, it’s been a little more complicated – a dizzying, multi-year, and often solitary experience. Some people are keen to share stories and cell phone pictures of the fire. Others are angry and distrustful, left wondering who – if anyone – is responsible for helping with recovery.

Nature of the beast

The Greenwood Fire was a fierce, even explosive, fire. On August 24, nine days after it started, the fire doubled in size, forming a stunning pyrocumulus cloud – a sure sign of intense fire behavior – that blew so far up into the sky it could be seen from Ely, more than 30 miles away. Firefighters were called off the front lines.

“There were days that the Greenwood Fire burned hot with rapid rates of spread. The changing wind directions made it hard to predict on some days,” said Nick Petrack, who is now the forest fire management officer for the Superior and Chippewa National Forests. “There were a few days I would classify the fire behavior as very high and somewhat extreme.”

Krista Schober’s experience aligns with that. That night they could see the fire across the lake from their home on McDougal Lake, where she and the neighbors stood outside in the dark, watching the fire from what seemed like a safe distance. The next day, the fire was coming straight toward them.

“The sky was crazy. It was like a movie scene, like a black angry devil coming for you,” said Schober, describing the evacuation. “It’s still not great to think about.”

Leaving Isabella

Isabella is more of an idea than a place. With just a few hundred year-round residents, Isabella has two bars, a few dog sled outfits, and endless dead-end logging roads. Nineteenth-century settlers called it “Horjoppi Kontri,” or “hurry-up country.” It’s a rugged land full of bogs, peatlands, and small lakes that are difficult to traverse and populated with biting, stinging bugs.

The Lake County Sheriff’s Office estimated that hundreds of people, including me, were evacuated from the Isabella area in 2021. Many people were summer residents with homes in distant cities.

Yvonne Wheale and her husband were at home in Esko when they got a phone call from a family member: The fire was spreading toward their 1970s-era family cabin on McDougal Lake. They decided to make a run for it. On the drive north, they strategized – who would do what, what to take, what to leave.

“We had a narrow window to work with,” she explained. “By the time we got there, we had an hour-and-a-half to get what we wanted and get out.”

For locals, many of whom had even less time to pack and leave, finding a place to stay was challenging and expensive. It was also surreal.

“They sent us to an evacuation center down by the North Shore, but they just handed us a bottle of water. So we went to the supper club in Finland. Half of the people in Isabella were there with nowhere to go,” Schober said, explaining that hotels everywhere were packed with summer tourists, and COVID-19 restrictions were in place.

“People were pulling out their phones, helping each other find places with friends or family,” she said. “People had pets outside in their cars. One guy was recovering from surgery. We just figured it out.”

Steve Wilson, who retired from the U.S. Forest Service, stayed behind. When a voluntary evacuation was issued for his area, he went to work preparing his property and turning on his wildfire sprinklers. Excerpts from his journal tell a terrifying story:

“By the time I came back outside, the bottom of the cloud had turned an angry orange-black. Later I was to learn this was when the fire went pyrocumulus, creating its own weather, lightning, and erratic fire behavior.

At that point, I knew staying was not an option. Even in the middle of the lake, in the water, I wouldn’t survive due to a lack of oxygen or volatile gasses igniting over the lake’s surface. And now the wind was gusting to 30 mph and debris [was] flying through the air, some of it looking suspiciously like ash.”

Weeks later, when people were allowed back into the evacuation area, there was much finger-crossing and holding of breath. The Lake County Sheriff had already contacted people who lost buildings. Some video clips of the McDougal Lake area, posted by volunteer firefighters to YouTube, offered glimpses of unrecognizable landscapes. The videos have since been taken down.

“You’re still hopeful driving in because you can see trees and green where the fire hop-skipped. Then we came to the last crest and saw everything gone. Like a bomb went off,” said Wheale. “And then the chaos started.”

Grappling with the unknown

During the first weeks of the fire, the news came easily. The USFS sent in a first-response communications team, who quickly set up nightly broadcasts with live updates on Facebook. Maps of the fire and video captured from the air made following daily fire progress easy.

Videos from the ground were harder to come by. One clip, taken remotely from a security camera, showed the fire approaching a McDougal Lake cabin — smoke undulating, back and forth, blowing embers under a black sky.

News crews were sent in from all over the country to report on the Greenwood Fire and the closure of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area, where several more, smaller fires were simultaneously active. Eventually, the fire was brought under control and in mid-September residents were allowed to return.

“Then communications went away. There was nothing,” said Michael Furtman, whose cabin survived with only a few trees on his property lost. However, he said he lost trees across the lake and islands from his property and he has neighbors whose properties are barren — the only things that remain are dead trees and the remains of burned outbuildings and cabins. “It just ended. It’s frustrating that there’s no news. Because this fire is not over for us.”

Wheale said communication with county, state or federal officials since the fire has been terrible. “Everything we learned, we learned from the news, but then that ended, too,” she said.

In fact, Isabella is what researchers call a “news desert.” To the east, community radio station WTIP, broadcasting out of Grand Marais, serves the east side of the forest. To the west, Ely enjoys two weekly newspapers — The Ely Echo and The Timberjay. In between, in Isabella, news travels by mouth, text, and occasionally by Facebook. The township of Isabella doesn’t even have a website.

“I was pretty satisfied with communication during the fire. It was handled excellently,” Furtman said. “Now they should be talking to us out there, telling us what the plans are for the forest. I know how to look, and I can’t find the answers.”

Wheale says she has questions. “It was chaotic, because no one knew what to do. We’re three years down the road, and it still feels that way … You would think there would have been a community meeting, a place to share resources. And that still doesn’t exist to my knowledge,” she said.

Schober, a bartender, is perhaps the closest thing to a central information bank. “And I don’t know anything,” she said, laughing. “I’m still trying to figure out what happened.”

‘You’re on your own’

“Lake County has been affected by wildfires every year for which modern data is readily available (since 1985), putting the probability of a wildfire in any year at greater than 99%.” -Lake County’s 2017 Hazard Mitigation Plan

A list of what’s left when a high-intensity wildfire eats a building reads like a dark and expensive nightmare: twisted, sharp-edged metal, asbestos-laden dust, dead standing trees that shed black branches like harpoons in the wind, crooked piles of cracked and crumbling concrete.

“What didn’t burn, melted. It was overwhelming,” said Wheale, whose property abuts the national forest. “We didn’t know what to do. No one reached out. Not the state, the county, not the Forest Service. Pretty much, you’re on your own.”

Wheale and her family have since carefully divided the materials into piles and hauled it away. It was expensive — much of it had to be taken more than 100 miles away for disposal.

“Our concern was to clean it up as best we could because we were considering building again. It was a lot of time spent researching. Days and days on the phone looking for help, only to get passed onto someone else.”

Furtman and his wife, Mary Jo, share Wheale’s frustration.

“I guess we’re a low-priority area. We’re not Ely, with fancy cabins and resorts. We’re just hicks in the woods with old mom-and-pop cabins from the 1950s,” he said. “You would think that after a fire of that magnitude, the county Firewise person would reach out to the property owners. I certainly still have plenty of fire worries.”

Aaron Mollin-Kling is the Lake County Firewise Coordinator, whose service area includes Isabella. A federal program funded through the state DNR, Firewise provides property owners with education and help for wildfire preparation — and sometimes funding to do that work.

He explains that the nature of his work is focused on helping people before fire. He confirmed with Project Optimist in April that he has not contacted property owners affected by the Greenwood Fire. However, he has spoken with property owners who reached out to him with questions.

Matt Pollman, Lake County’s Emergency Manager, said the fire didn’t qualify for a FEMA designation.

“For FEMA to be activated for individual assistance, at least 75 dwellings would have to be destroyed — primary residences only, not leisure cabins. And of those 75, 40% would have to be uninsured. When that happens, the state and federal governments share a cost share of 25% and 75%, respectively, which helps with debris costs. This help is only activated when the governor declares an emergency,” he said.

Christine McCarthy, Lake County Environmental Service Director said, “When people called, we tried to answer as many questions as possible regarding waste disposal, but this was not an organized and funded cleanup. Our department does not have the staff to reach out in a remote location and educate everyone.”

A USFS scientist provided Project Optimist with an information sheet created in early 2022. The sheet lists resources for private landowners at the bottom.

Superior National Forest public affairs officers declined to address questions from Project Optimist about communication concerns with property owners after the fire.

Wheale already knows all this. Happily, she said she finally found help from her insurance agent, who told her he was a little shocked by her claim.

“He told me they don’t get claims like this from the Midwest," she said. "These kinds of fires happen out west, where the fires are bigger and hotter. I told him, ‘Well, now it’s here, and I don’t know where to begin.’ Thank God he did. He was the most helpful person I talked to.”

Replanting and rebuilding

Furtman is reconsidering his relationship with Superior National Forest and wildfire. Not necessarily by doing more Firewise preparation, or installing a wildfire sprinkler system — although both are in the plans. Instead, Furtman is focusing on replanting.

The fire stopped mere feet from his cabin, and at this point, he said, who would want to buy a cabin in a moonscape? “I selfishly want my view back,” he said.

As an outdoor writer and nature photographer, Furtman knows his way around the woods, so to speak. “I pestered the Forest Service and they hooked me up with The Nature Conservancy. We planted 10,000 trees on our lake last year,” he said.

Using his dock as a staging area, he helped transport seedlings and groups of tree planters across the lake in a boat.

Wheale has shifted her concern to the shoreline of her lake property, where they have left the dead trees standing to hold the soil in place. Dead white pine soar more than 100 feet in the air, way too big for their chainsaws or know-how.

“We’re looking at building as our going-forward plan,” she said.

This story is part of Project Optimist's wildfire series. It was edited by Jen Zettel-Vandenhouten and Nora Hertel, and it was fact-checked by Jen Zettel-Vandenhouten.