Das BioHaus models sustainable living where you might not expect it

A German camp in Minnesota features 3 keys to low-energy living.

BEMIDJI - A 16-year-old building for campers in northern Minnesota holds lessons on how we can reduce our energy use and build more sustainably.

Throughout the summers, up to 24 students at a time live in Das BioHaus and practice German in a corner of the Concordia Language Villages near Bemidji. They learn about stormwater, share solar-heated water for showers, manage the blinds to help control the building’s temperature and get an inside look at the power of insulation and heat pumps.

These lessons from the Waldsee - the German language village - were cutting edge when the BioHaus opened in 2006, and they’re still useful today. The building won a Minnesota Environmental Award and was the first certified German Passive House building in the Americas. (The Passive House model is characterized by building elements that decrease energy needs to as low as 10% what traditionally-constructed buildings use.)

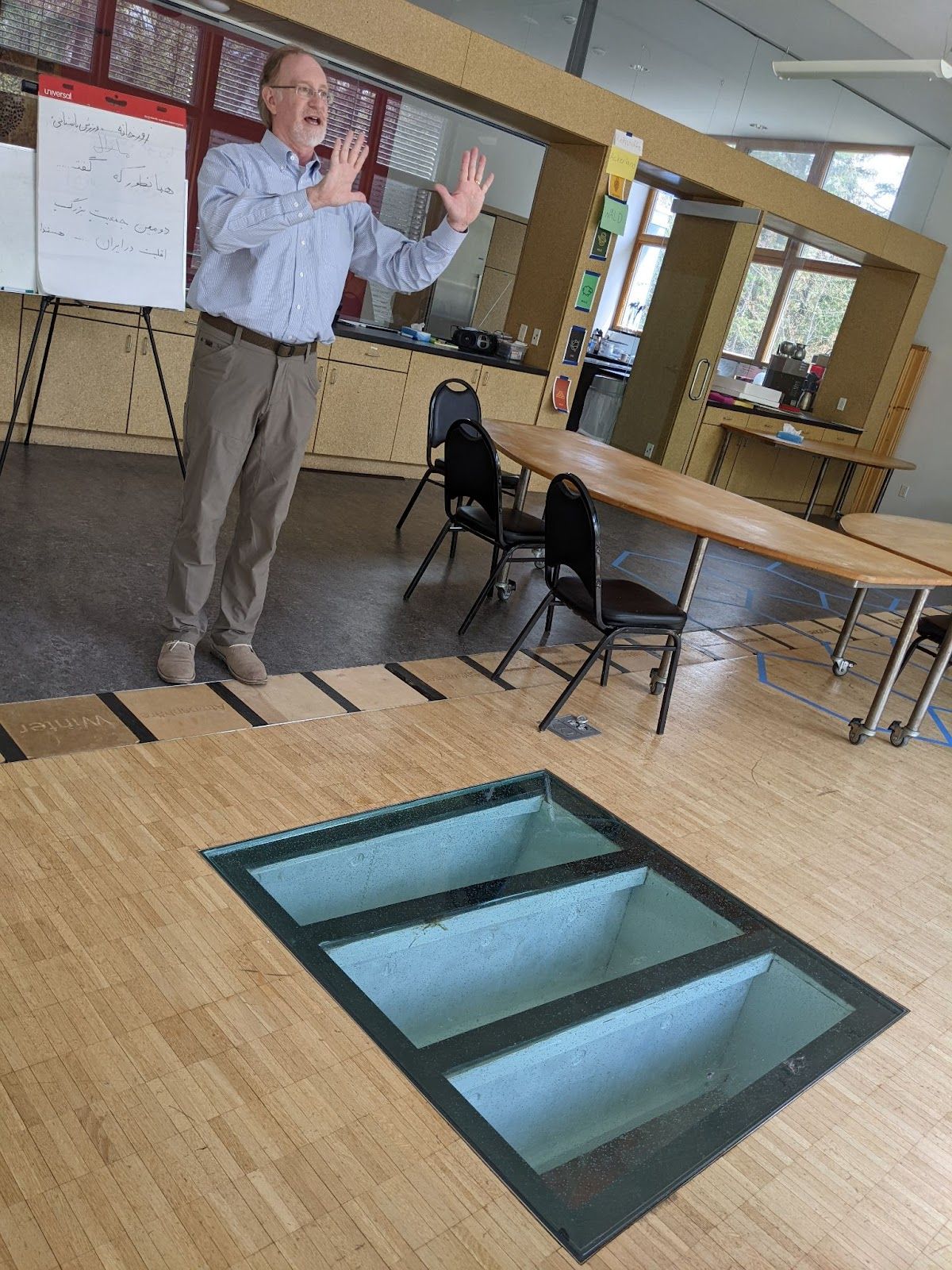

“It really just takes sips of the electricity,” said Warren Schulze, director of operations at Concordia Language Villages, during a tour in late May, just before the start of the summer camp season. There weren’t any children around, and birdsong carried through the clear air.

The elements that make the BioHaus unique are important today as governments, businesses and individuals strive for energy efficiency and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Emissions from Minnesota’s residential buildings rose 32% from 2005 to 2018, despite the state's bipartisan Next Generation Energy Act that sought to reduce all greenhouse gas emissions statewide by 15% between 2005 and 2015.

Nationwide, residential and commercial buildings are responsible for about 29% of all greenhouse gas emissions.

BioHaus is not 100% off the grid. Energy-generating solar panels may eventually close the gap.

“It would not be difficult to make this building 100% self-sustaining,” Schulze said. “We build as the money comes, and we haven’t quite had the money to add the photovoltaic panels yet.”

Photovoltaic panels turn energy from the sun into power. Hydronic solar panels, which the BioHaus does have, heat the water used in the building for showers and other domestic tasks. When there’s no sun in the forecast, the campers have to plan and share whatever hot water stores they have.

“The architect explained it best: A Passive House is not passive living. It’s active living,” Schulze said. The building was designed by Swiss-born and Twin Cities-based architect Stephan Tanner.

Much of the funding for the BioHaus came from the German government and many of the materials in the building came from Germany including its triple-paned and argon-filled windows.

Argon gas adds insulation to the windows. And insulation is a big part of what makes the BioHaus so efficient. Here’s a rundown of three different components in the building that can bring energy efficiency to new construction and renovations.

Insulation

The BioHaus uses some innovative insulation, including a green roof, in which plants and soil help reduce lost heat from the top of the building. Technically, the building didn’t need a green roof, because there was already a thick layer of insulation. But the green roof is also a teaching tool for the students who visit.

“It's a great learning opportunity for talking with kids about stormwater, you know, where does all that go,” Schulze said. “Even in the U.S. that has become a thing. How much hard surface do you have on your property, especially commercial properties, malls, with their parking lots and their big roofs.”

The building also has foam and panel insulation, including vacuum-insulated panels initially developed by NASA for heat shields in space. These panels are also used in refrigeration. But they didn’t quite take off in the U.S., because they are fragile, Schulze said.

“We were willing to try it. And our contractor here was willing to try it,” he said.

Air circulation

With all that insulation, the BioHaus is very well sealed. Some older homes developed mold problems when they were sealed without good circulation. But Passive House engineers revisited the challenge and incorporated air exchange systems, Schulze explained.

There’s a silver tube that sticks out of the ground to draw in fresh air that gets circulated underground and warmed up before it’s brought into the building.

In all its years, the BioHaus air exchange system has tested clean and clear of buildup or mold.

Temperature control

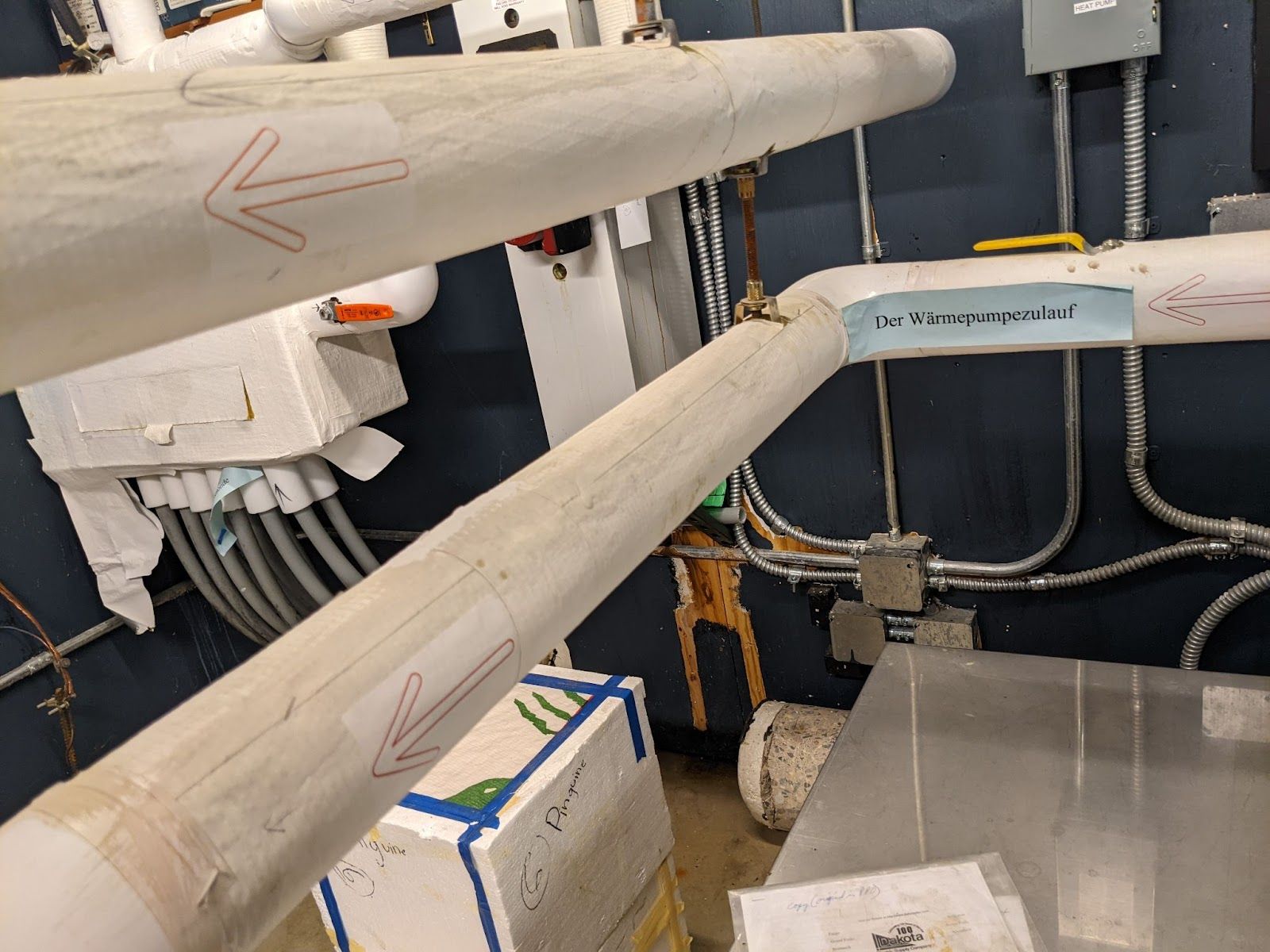

There’s space in the BioHaus mechanical room for a group of students to study the large tubes and meters of the ground-source heat pump. The system uses heat and cool air from the earth below the frost line to warm or chill air circulated in the building.

Warmth is pumped into the floors to heat the building. Sun enters through the south-facing windows to provide heat as well.

When it’s too hot, campers can adjust shades outside the windows and the temperature from the heat pump. It can’t change on a dime, but that’s part of the experience. That's the active living required in a Passive House.

Ten years after the BioHaus opened, architect Stephan Tanner reflected on its construction and encouraged the students who pass through the camp to be change leaders and take on the environmental challenges of the day.

"We have to become WORLDHOLDERS – each one of us,"Tanner wrote in a post published by Concordia Language Villages. "We have to become part of a global society that has the same equitable target and goals for all. We must understand that resources are limited and that climate action plans and implementation projects have to be local."

This story was originally published in the Project Optimist newsletter on Nov. 30, 2022.