Drawn by Nature: Find funky fungi late summer through early fall

Late summer and early fall rank as the peak time for many wild mushrooms – especially edible varieties.

Head out on a hike in early September, and you might be lucky enough to spot speckled peach and red-orange mushrooms that look like something out of a fairy-tale book. Fly agaric mushrooms fall into the amanita family and are considered toxic, but they get points for style and looks.

These days, like a 1970s flashback, you can find mushroom illustrations on just about everything from clothing and kitchen towels to phone cases and wall art. Fungi have reached a food-fad moment shared with lemons and avocados.

I used to assume that finding fungi in the wild was reserved for the damp days of spring when people fervently search for morel mushrooms. With their caps filled with nooks and crannies that soak up butter like crumpets, morels can be among a forager’s most coveted meals as they sizzle alongside roasted spring ramps and fiddleheads.

But here’s the surprise: Late summer and early fall rank as the peak time for many wild mushrooms – especially edible varieties.

Fall foraging can be busiest season

My introduction to the surprisingly diverse world of fungi began with a hike alongside Kevin Doyle, who founded Forest Mushrooms in Collegeville more than three decades ago. It has grown to become the Midwest’s biggest specialty mushroom farm over the past three decades, growing its own oyster and shiitake mushrooms and drying wild mushrooms collected by skilled foragers.

He pointed out a number of edible mushrooms in the woods of Collegeville. Chanterelles can be among the easiest to spot with their yellow-orange stems and fluted cap. Other edible mushrooms include black trumpets, oysters, nubby hedgehogs, shaggy lion’s mane, king boletes, puffballs, and reddish lobster mushrooms.

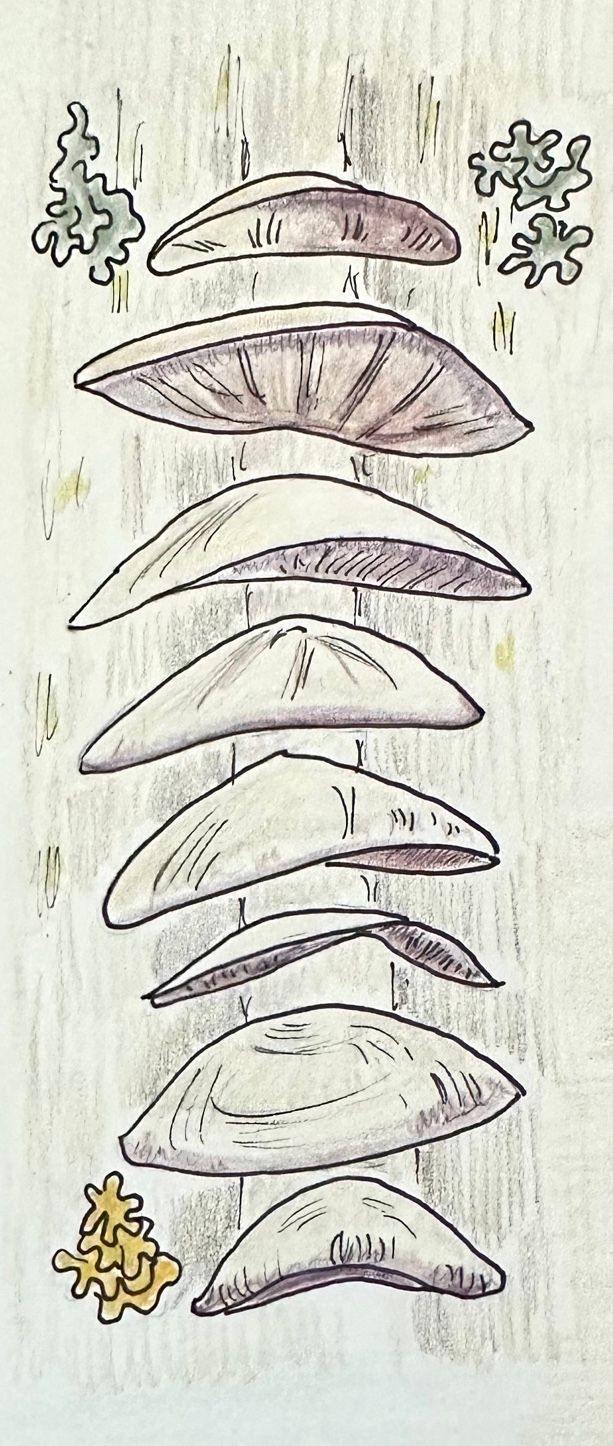

So-called shelf mushrooms stack along fallen trees or tree trunks. Brown-colored hen of the woods (also known as maitake) and orange-and-yellow chicken of the woods, grow in rounded, ruffled layers. Sheer size makes these a motherlode for foragers.

It can be fun to study what’s growing, especially when you’re simply observing and not worried about identifying safe, edible species. You may find a vertical line of shelf mushrooms resembling the vertebrae on human spines or stumble upon oddities such as witch’s butter – a jelly-like fungus, scrambled egg slime, or the aptly named dead man’s fingers. Those may not make it on your kitchen towels, but the “ew” factor might get you into the Halloween spirit a little early.

Get involved and learn more

“Mushrooms of the Upper Midwest” by Teresa Marrone and Kathy Yerich can help you identify your finds. Posting photos of fungi on the iNaturalist citizen science app can also help you figure out what you found while also mapping its location with GPS. That GPS can be handy if you want to make hunting mushrooms an annual tradition. The Minnesota Naturalist Facebook group can also help you figure out curious finds of all kinds.

If you want to forage for edible mushrooms, team up with an expert to help you identify safe and tasty fungi while avoiding dangerous – even deadly – look-alikes. They can also show you when a mushroom is ripe and ready or drying out and past its prime.

With hundreds of members, the Minnesota Mycological Society brings together both curious and passionate fans of fungi. The group offers classes for members during the year and hosts forays, which are guided hikes to find edible mushrooms.

In central Minnesota, Avon Hills Folk School sold out four guided mushroom hikes in August, but another session or two may be added in September if rain brings more moisture and better growing conditions.

Twin-Cities-based Gentleman Forager leads mushroom hunts within a 2.5-hour radius of the Twin Cities, as well as special events centered on cooking with foraged ingredients. Mushroom hunts usually conclude with baking a pizza topped with some of the fresh finds.

Help migrating birds fuel up

As summer winds down, humans aren’t the only ones foraging in woods and gardens for food. Pollinators are feasting on as much nectar as possible before hibernation, and birds are loading up on calories before migrating to the southern U.S. or Central America.

Hummingbirds are among the earliest migratory birds to leave, starting their journey by the end of August or early September. They need to gain 25% to 40% of their body weight before traveling to keep up with a migration heart rate of 1,260 beats per minute and wing flaps of 15 to 80 times a second.

With that kind of energy required to travel, it’s no wonder that refueling stops in places like St. Cloud’s Munsinger Clemens Gardens can turn into feeding frenzies. Few sounds compare to the buzz of hummingbirds whizzing past your head.

If you have feeders with nectar for hummers or seeds for songbirds, it’s good to refill them often as birds are on the move. If you want to learn more or to track hummingbird migrations in the fall and spring, check out Hummingbird Central.

Who's behind this column?

St. Cloud-based Lisa Meyers McClintick has been an award-winning journalist and photographer for more than 30 years. A lifelong nature nerd, she joined the Minnesota Master Naturalist program in 2021.