Drawn by Nature: Seeds are mini marvels of design

Hand-collect seeds for affordable, biodiverse gardening, writes Lisa Meyers McClintick.

Language in this column was updated on Sept. 17, 2024 to make the adaptations of seeds clear. It was originally posted on Sept. 11, 2024.

As summer wanes, so do its flowers, closing blossom by blossom after butterflies, bees, and other insects have pollinated them. Plants might look spent and untidy in this process, but practice patience as plants produce seeds for the next generation.

I’m a collector of seeds, a habit I picked up from my dad decades ago. We empty from our pockets crumpled baggies with tiny daisy seeds or prickly echinacea seeds or we pull out a few pods from a lupine or false indigo. (I don’t recommend leaving the latter on a kitchen counter without warning your family. It looks like an unwelcome surprise left by the cat.)

Whether you’re collecting seeds to expand your garden or sharing and swapping with friends and neighbors, seed-collecting can be an easy and economical way to garden and to connect with others. We’ve saved and shared seeds such as cosmos, zinnias, calendula, hollyhocks, and more.

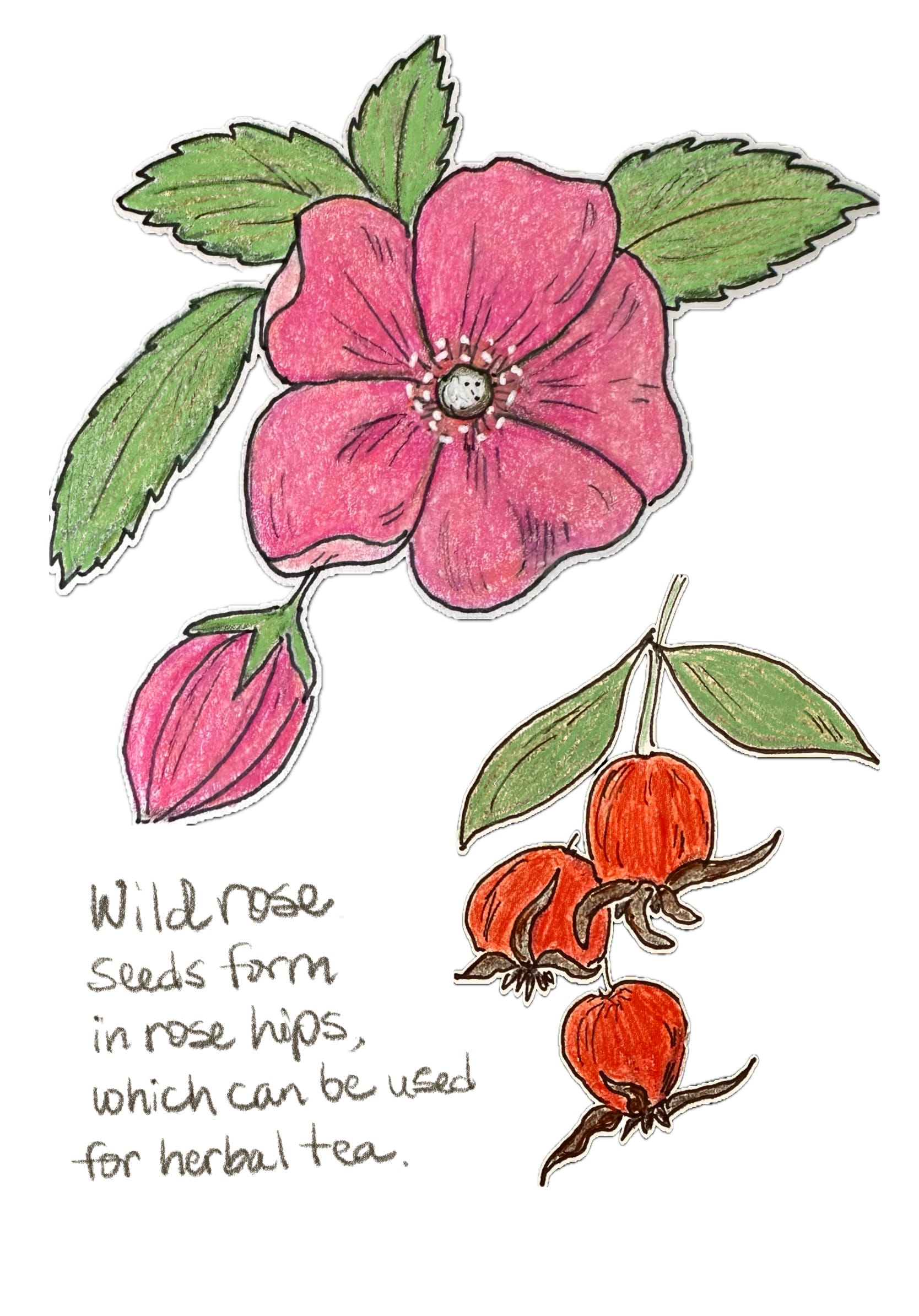

This time of year, I study the transformation of flowers into well-adapted seeds. Circular discs of hollyhock seeds remind me of old-time carousel slide projectors. Itty-bitty poppy seeds rattle in their pods. Echinacea seeds form in spiky pods.

Butterfly weed, which is a vibrant, orange-flowered milkweed, forms 3-inch pods on plants until they split open to release the seeds on downy parachutes that float into the wind to new places to land and take root.

Seed collecting or swapping also helps if you’re aiming to add native plants that hold up to drought or rain. Converting a section of grass into a native garden creates a refuge for pollinators, which helps with biodiversity and can draw more wildlife.

Seeds seem to roughly fall into these categories based on my own observations:

Clingers: If you’ve ever walked a dog in the woods and cursed the cockleburs and pickers that snarl into tails and onto haunches, you’ve experienced the wildly effective form that inspired the invention of Velcro. These seeds hitchhike to new locations on humans and animals.

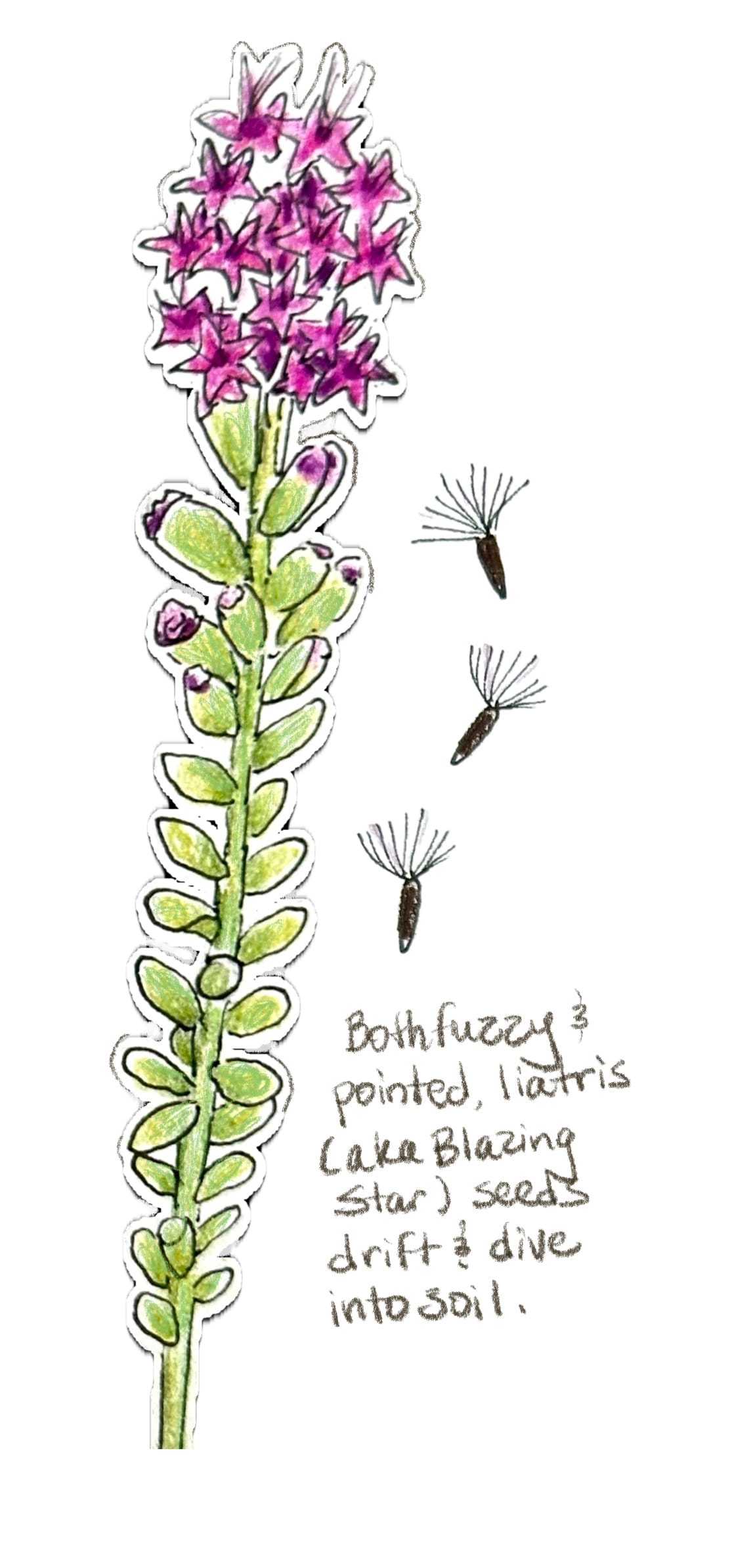

Dirt divers: Narrow or spiky seeds like echinacea that can stab into soil and drill their way beneath the surface to sprout.

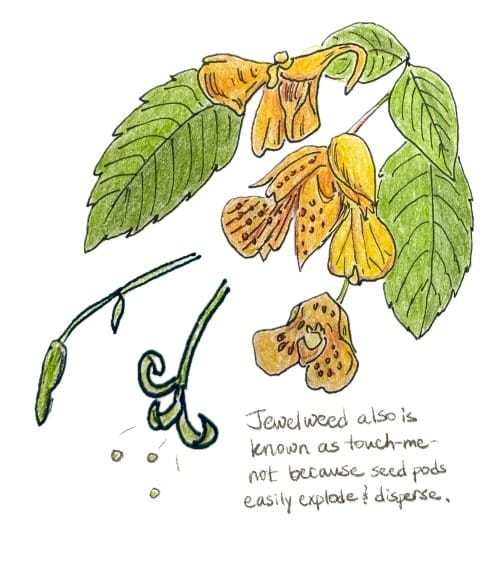

Exploders: There’s a small window for successfully collecting seeds in this category. They need to be mature, but gathered before their pods naturally explode open to scatter the seeds. Attuned seed-collectors say you can hear pods bursting open in a field of lupine plants. Along ponds and low-lying areas, jewelweed, also known as touch-me-not, has seed pods that explode at the slightest touch.

Gliders and drifters: Inventors have studied and mimicked shapes and aerodynamics of seeds in this category. Think of how downy dandelion seeds and milkweed seeds drift on the wind like tiny parachutes.

Biodiverse landscapes help wildlife

We have mauve-flowered common milkweed in our yard. It showed up on its own, and we’ve learned not to pull it out. We watch for the tiny yellow, black, and white-striped monarch caterpillars that depend on milkweed as its host plant. Some years we find close to a dozen, although this year seems unusually low on butterflies, which were affected by last year’s drought.

Awareness has grown for the importance of vital host plants, such as milkweed. Monarchs aren’t the only butterflies that need specific plants, and diverse native plantings assure more host plants. A healthy garden should also have enough plant species so something is continuously blooming from early spring when the first bees emerge through fall when migrating hummingbirds, monarchs and bees need food for their journey or a healthy hibernation.

More plants support more insects, which support more amphibians and birds, which support more wildlife. Another bonus: native plants require less water and maintenance and can better handle weather extremes, such as last year’s drought swinging to an overload of rain this year.

Drawings by Lisa Meyers McClintick.

Volunteer, learn more about natives

Public parks and wildlife refuges rely on volunteers to hand-collect the seeds that can help restore or expand native prairies. Budgets can’t cover buying only commercial seed for the vast spaces they are seeking to restore and seed supplies may be limited.

Volunteering to collect seed by hand provides a chance to learn about seeds from mentors and to discover the native plants you enjoy the most, from licorice-scented hyssop to wild mints. Many of the biggest seed collection efforts coincide with National Public Lands Day, which is Sept. 28.

This is the 30th year of the effort, which is the nation’s largest single-day volunteer project. Projects from collecting seeds and planting pollinator gardens to planting shrubs and trees are planned across the state.

You can also start small at home. Plant a small pocket prairie in your yard, collect and share seeds from your own garden, start a neighborhood swap, join a local garden club, or join a community garden.

Whether you stick to native plants, crave showy hybrids, or a mix of both, gardening beautifies where we live, sows connections to others, creates seeds for the next generation, and nurtures more creatures than we realize.

Dig deeper for more inspiration

Minnesota Board of Water and Soil Resources provides a wealth of information and some grant applications for everything from creating a small garden of native plants to bee or pollinator lawns.

Northern Gardener, a website run by the Minnesota State Horticultural Society, has “Gardening for the Planet” webinars and how-to articles on seed collecting, storage, starting seeds, and planning a seed swap in its resource hub.

Prairie Restorations's Princeton Garden Center offers a vast collection of native seeds and a large selection of gardening, homesteading, and nature books.

MN SEED Project often gives away native seeds, sponsors seed exchanges, and hosts seed processing events, which guide participants in cleaning, prepping, and storing seeds.

Guidelines for collecting native plant seeds

- Check local parks for volunteer collecting opportunities.

- Get permission before collecting seeds on public or private properties.

- Harvest when the weather has been dry.

- Only harvest a third of the seeds. Allow the rest to naturally reseed or to feed wildlife.

- Carry pre-labeled paper envelopes or paper lunch bags for collecting. Plastic bags trap lingering moisture and compromise seed quality.

Who's behind this column?

St. Cloud-based Lisa Meyers McClintick has been an award-winning journalist and photographer for more than 30 years.

The second edition of Lisa’s "Day Trips from the Twin Cities" hit bookshelves June 4. When she’s not writing, she’s in the woods taking photos, working on her nature journal and volunteering with the Minnesota Master Naturalist program.

This column was edited by Jen Zettel-Vandenhouten.