Drawn by Nature: Taking a liking to lichens

While often overlooked, lichen are prevalent in Minnesota, with an estimated 700 to 800 species in the state.

Pay attention, and you might have noticed a vibrant shade of yellow-orange radiating across many rock ledges along Minnesota’s North Shore. I remember calling out, “Hey, we match!” years ago as I stood in orange Keen sandals in the exact same shade as elegant sunburst lichen.

This often-overlooked organism catches the attention of many people for the first time at popular stops such as Gooseberry Falls State Park where the river meets Lake Superior or along the breakwater trail at the harbor in Grand Marais.

Elegant sunburst lichen adds color to the drabbest of cloudy days and the muted landscape of Minnesota’s shoulder seasons, but it’s only one of thousands of lichen varieties that add color and textures across the state.

Joe Walewski, teaching and learning coordinator at Wolf Ridge Environmental Learning Center, started noticing lichen when it was literally in his face while rock-climbing and authored the “Lichens of the North Woods” field guide.

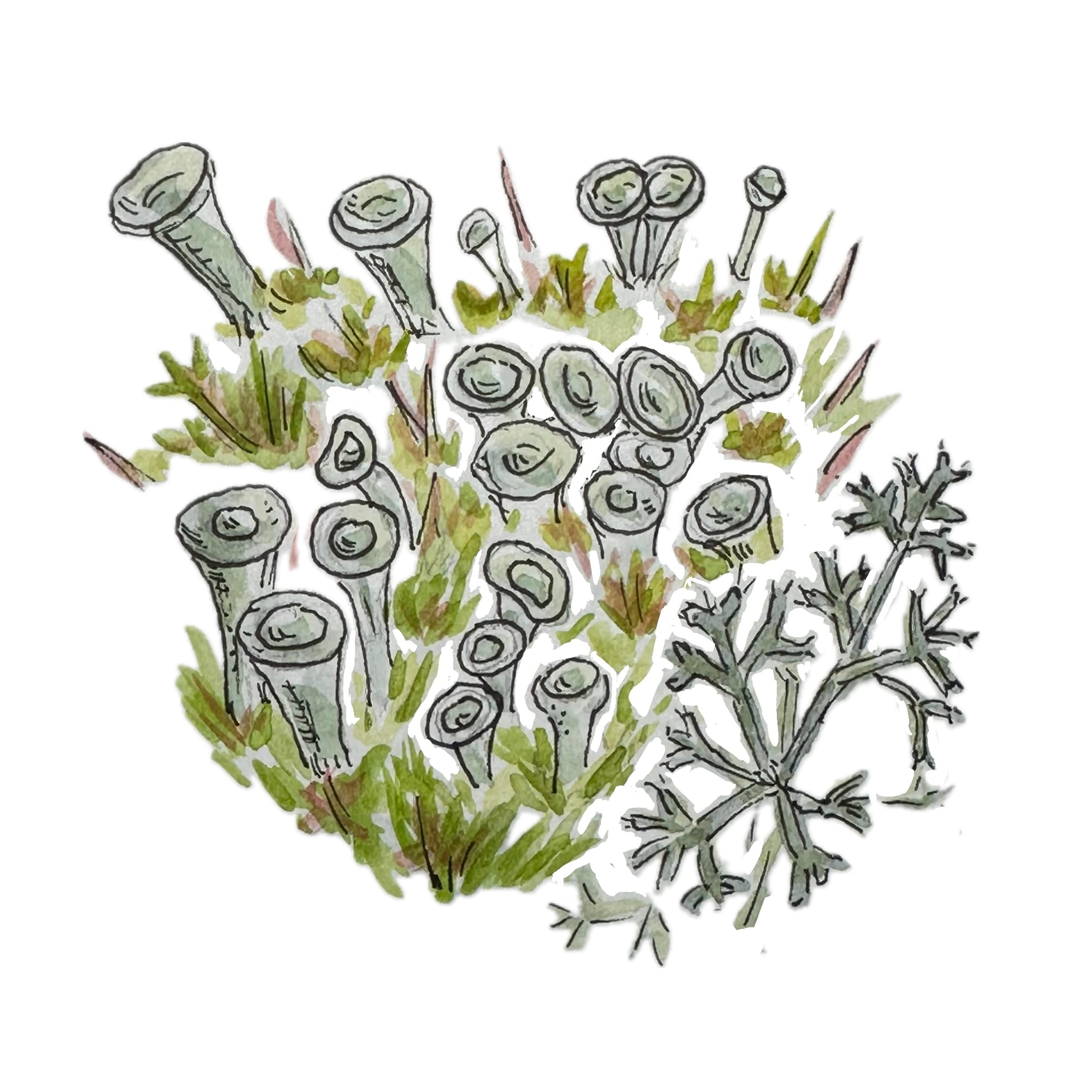

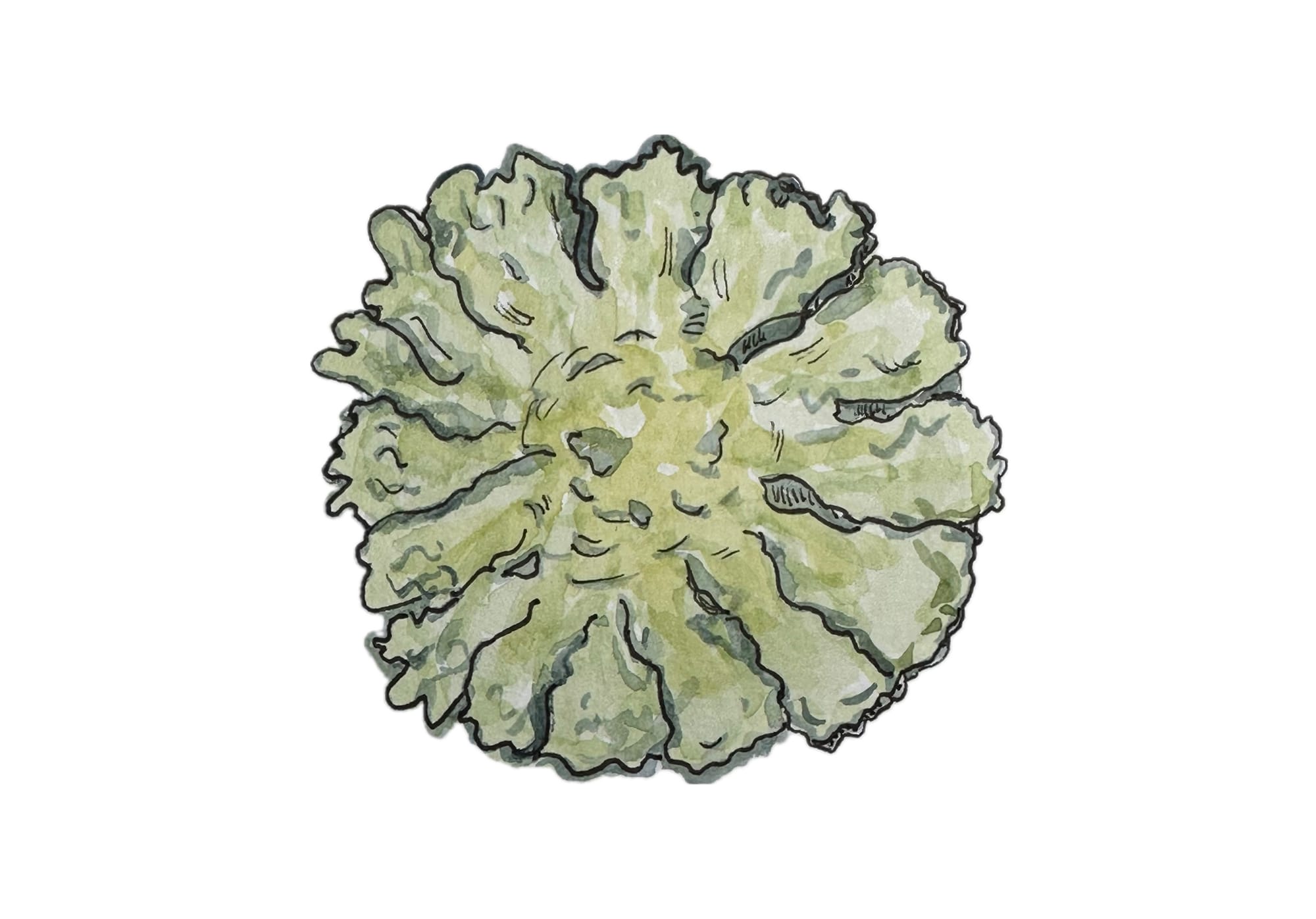

He introduced readers to these organisms that can show up as lacey white circles and deep yellows dotting gravestones, inky ruffles or bright oranges anchored onto rocks. Ruffle-edged greens and grays wrap trunks of trees, while tiny cups might sprout from the earth like delicate golf tees. In damp sections of the boreal forest, lichen may tuft along tree branches like Spanish moss in southern states.

“Once a person opens their eyes, lichen are everywhere,” Walewski said.

A complex organism

His book is one of only a handful of guides on lichens in the country. An estimated 700 to 800 kinds of lichen can be found in Minnesota alone. The diversity and concentration of lichens increases in old-growth forests and along ancient rocks, such as those in the Boundary Waters.

Part of why they’ve been overlooked is the difficulty categorizing them. Lichens are not a plant even though the bushier species might be mistaken for moss. Instead, lichens comprise a complex combination of fungus plus algae and/or cyanobacteria.

The fungus absorbs water, provides structure, and protects lichen as it attaches to trees, rocks, and earth. Algae and sometimes bacteria use sunlight to generate nutrients that fuel its slow and steady growth. Some lichens might only grow 0.5 mm a year – the diameter of the average pencil lead.

Puzzling over which of the connected organisms benefits the most and which one might be in control adds to the scientific intrigue of lichen, say Zan Tomko and Elaine Larson, volunteers with the University of Minnesota Extension master naturalist program.

To help increase information available about lichens, the two friends from the Twin Cities set up the Minnesota Lichen Map project. It consolidates the state’s lichen photos uploaded by more than 2,000 observers who have contributed to the popular iNaturalist app. The phone app makes it easy for citizen scientists to post photos and identify lichen finds, as well as photos of plants, animals, and fish.

They encourage using a macro lens or a handheld loupe or magnifier to marvel at the intricate textures, patterns, ruffled edges, and wispy beards of different lichen species, which come in colors such as blue-gray, vivid orange, brown, white, neon yellow or green, and spots of red.

The app also shows on maps where people can find different species by searching for names such as lipstick powderhorn, boreal beard, crumpled rag, sea storm, powdered sunshine, and British soldiers.

Many of the species that grow on rocks and trees (and wood structures and gravestones) can be seen year-round and often in colonies with other kinds of lichen, moss, or fungi. Lichen species that grow on the ground can be easiest to spot in early spring or late fall when winter snow or summer foliage aren’t obscuring these diminutive displays.

Small but mighty filters

If you live in an area with multiple kinds of lichen, that’s a good sign. Lichens works as natural air filters, absorbing pollutants such as sulfur dioxide. The hardiest lichens survive droughts and winter freezes. Some showed their resilience by growing back after being exposed to the conditions of outer space during a 2005 trip.

Humans have yet to commercialize lichens and propagate them for profit — another reason they may be overlooked — but different species can break down rock and create soil, nourish animals (and occasional humans), provide medicinal uses, offer nesting materials for birds, and dye natural fibers.

Despite these diverse uses, more has yet to be learned about lichen, from how it functions to how else it benefits the natural world. That remains a daunting task. The National Park Service estimates there are more than 3,600 lichen species in North America alone, and more than 19,000 species worldwide.

“Eight percent of the biomass in the world is lichen,” said Tomko. “By observing and scouting for lichen, you will begin to have a deeper appreciation for these slow-growing, beautiful organisms.”

Lichens to look for

Look for lichen on rocks, tree trunks and branches and underfoot on soil. Here are some common species you might see:

Elegant sunburst lichen: Arguably the easiest to spot, elegant sunburst lichen covers dark rock along Lake Superior with bright orange color.

Green shield: These rounded lichens with intricate ruffled edges can be seen on many tree trunks.

Rock tripe: Green, dark brown or an ashy gray, these leafy-looking kinds of lichen attach to rocks.

Bearded moss: These lichens can be seen dangling from trees in moist areas like Grand Portage State Park.

Firedot: These little yellow-green dots often show up in cemeteries.

Take a hike

- St. John’s Arboretum, Collegeville. The iNaturalist app can identify names of lichen along the trail to the Stella Maris Chapel.

- Quarry Park and Nature Preserve, Waite Park. Look for lichens polka-dotting massive granite ledges and grout piles or wrapped around trees.

- North Shore state parks. Check the rocky state formations along the Lake Superior shore, as well as public beaches and harbors. Trails around the Chik-Wauk Museum and Nature Center on the Gunflint Trail also are good, as is the path to the Grand Portage waterfall.

- Blue Mound State Park, Luverne. Visitors to rosy quartzite that juts out of the prairie (popular with rock-climbers) can find plenty of lichen. Across the South Dakota border in Palisades State Park, there’s a downloadable lichen hike.

- Any cemetery whose gravestones stretch back to the 1800s.

Join the mapping project

If you spot lichen around your home or in local parks, add your photos to the Minnesota Lichen Map through the iNaturalist app. You can find more tips for finding lichens on the map’s journal page.

Who’s behind this column?

St. Cloud-based Lisa Meyers McClintick has been an award-winning journalist and photographer for more than 30 years. A lifelong journal-keeper and nature nerd, she joined the Minnesota Master Naturalist program in 2021.