Extended Producer Responsibility shifts recycling cost, promises investment

Minnesota wants producers to pay for recycling. How has that worked in Canada and the European Union?

This story was updated on Thursday, Jan. 30, 2025, to correct the description of Circular Materials and to more accurately reflect the organization's service area. Project Optimist regrets the errors.

Recycling costs have grown, North American experts say, at a time when plastic consumption booms and packaging is increasingly made up of plastic.

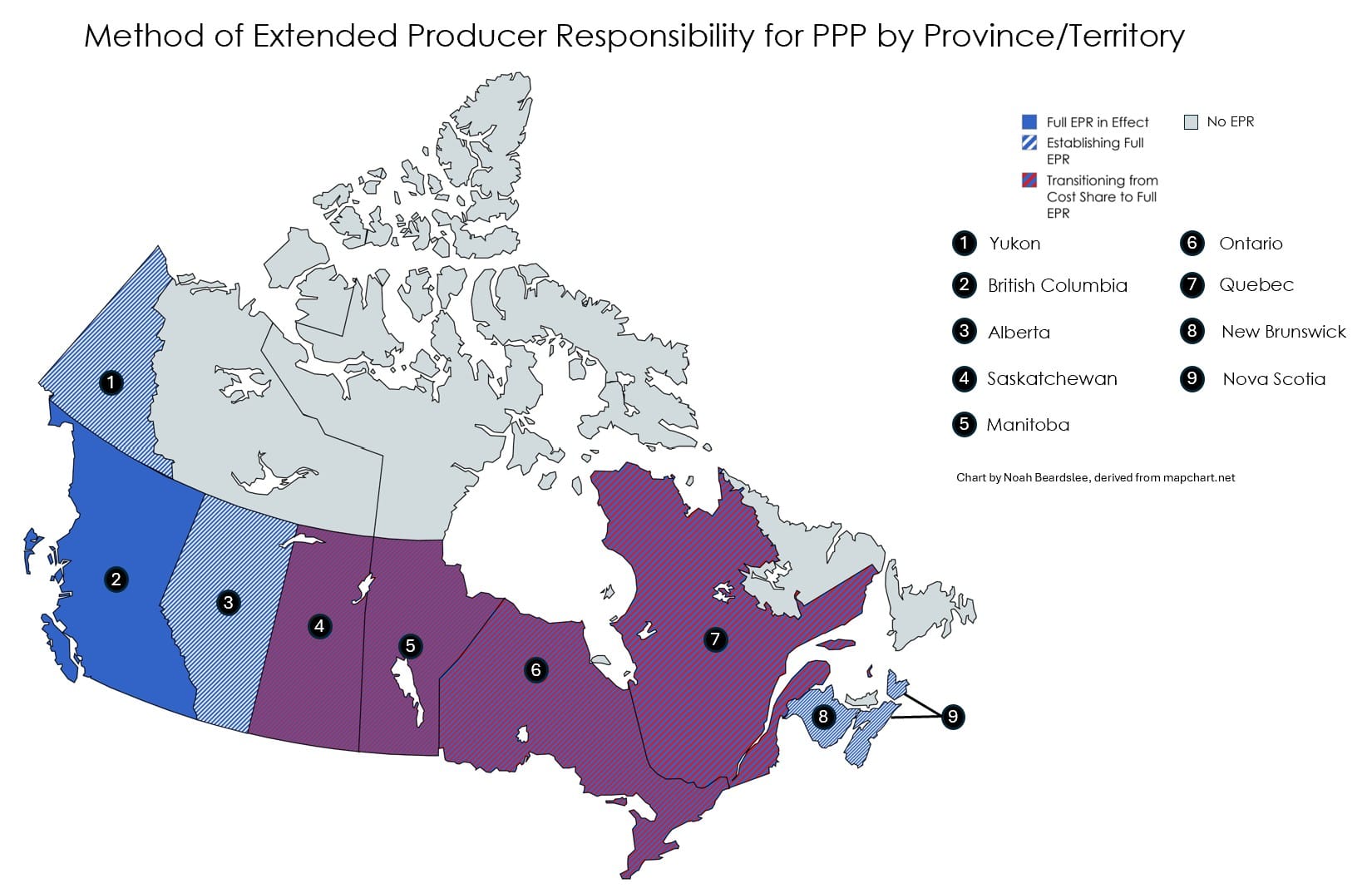

Against this backdrop, Minnesota passed a law in May 2024 to make industry foot the bill for the packaging waste it introduces to the marketplace. With that, Minnesota joins the ranks of four states, most Canadian provinces, and European nations with similar laws on the books.

Get solutions journalism in your inbox

Sign up for Project Optimist's weekly newsletter.

It's free. No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

What is Extended Producer Responsibility?

Governments around the world use Extended Producer Responsibility laws, first enacted in Germany in 1992, to cover the disposal of tires, mattresses, e-waste, used oil, batteries, and hazardous household waste.

Packaging and Paper Products (PPP) are specific types of EPR laws, and what they cover varies. Typically, it's cardboard, plastic, glass, and metal. However, the law can extend to leaflets, newspapers, or beverage containers.

Allen Langdon is CEO of Circular Materials, a nonprofit organization that oversees EPR implementation in parts of Canada. He said EPR was introduced as recycling rates were flat or declining to “more efficiently organize recycling activities” and run them on a system-wide basis rather than a patchwork.

Since the European Union implemented EPR, recovery rates for packaging waste exceeded targets and increased from 54.6% in 2005 to 63.6% in 2011, according to a white paper from INSEAD Social Innovation Centre.

Obstacles to enforcement

Part of what makes PPP enforcement the greatest challenge compared to other EPR programs is, “nobody sells packaging, they sell the product,” whereas with other EPR programs it is obvious who is obligated, said Brienne Bennett, the senior waste management coordinator with the Saskatchewan Ministry of Environment.

So is this type of EPR worth it?

Bennett thinks so.

“It’s (packaging) not as, maybe, dangerous for the environment for the size of the material; like a piece of paper is not as dangerous as a drop of oil,” Bennett said. “But when you think of the big picture, how much energy it takes to create that piece of paper — all of the energy, the cutting down the forest, and then all of the waste that's created and where it ends up in the environment — I think it could be as hazardous”

The benefits and trade-offs of EPR follow its structure, which varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

To carry out EPR, producers — which can include manufacturers, importers, or retailers — typically form a Producer Responsibility Organization (PRO). Whether nonprofit or for-profit, a PRO collects data on the volume of material injected into the market and uses the data to assess fees to cover the cost of compliance, recycling, and in some cases education.

"Businesses are making this material," said Langdon. Circular Materials, the organization Langdon leads, is a PRO and back-office support for several Canadian provinces and territories. "They have the knowledge of what the material is made-up of, and they should be responsible for its end of life.”

Producers could provide recycling services individually, but because of how much work it takes, no one in Saskatchewan does, Bennett said.

Transition to ‘Full EPR’

Some provinces, like Saskatchewan, have had packaging and paper products EPR for a decade or more. Now many are in the middle of a shift to “Full EPR” — where producers take operational control of recycling. Even those that formerly had “cost-share” systems — where business and government foot the bill, and municipalities provide the service — will make the transition.

Langdon said the nature of packaging has changed over the decades, and involves more rigid and flexible plastics that require investment in recycling technology that, “would probably make more sense on a larger scale; would be more difficult on a municipality-by-municipality basis."

A province-wide, standardized recycling system where the same materials can be collected everywhere is an advantage Langdon and Bennett said Full EPR has. The alternative causes confusion about what materials can be recycled, which may cause skepticism of recycling, Langdon said.

Project OptimistJen Zettel-Vandenhouten

Project OptimistJen Zettel-Vandenhouten

Business across national and provincial lines

Across the pond, EPR expert Nathan Kunz said European Union directives hold member nations to EPR, but they have a lot of flexibility in how it’s implemented.

While some stakeholders, cited in a paper he co-wrote, said this variation gave producers high administrative costs to work across national lines and lessened incentive to redesign products, local control made the laws easier to enforce.

In a broad sense though, a large number of jurisdictions with EPR can incentivize its wider adoption.

“It actually makes it easier for [businesses]," Bennett said. “It reduces their red tape, if you will, to participate similarly in every single province, instead of having to do different things in different provinces.”

This was evident in Nova Scotia several years ago when the province had not started to participate in EPR. Residents' taxes paid for recycling, and they also paid higher prices for products as a result of EPR in other provinces – essentially they were “paying twice.”

Concern about this drove support for EPR among Nova Scotia municipalities, according to reporting from CBC, as the province implements it.

A shift to EPR can mean lower costs to municipalities in provinces that adopt it. Toronto spent 50 million Canadian dollars ($34.7 million) on recycling before Circular Materials took over in 2021, according to the city's media team. But that comes with a caveat.

Project OptimistLisa McClintick

Project OptimistLisa McClintick

Cost to consumers and taxpayers

In municipalities where recycling costs are lumped into the property tax, municipalities will just put that money to other uses, but specific recycling taxes, if they existed before EPR, could go away, waste expert Calvin Lakhan said in an interview with the CBC.

The shift from taxpayers to producers also means consumers eat the cost.

“It's a sort of tool to make people responsible for their purchases,” Kunz said of this cost transfer, “and I think that's good because otherwise it gives the impression that it's free, and the state is going to pay for it.”

Although businesses may bask in public approval by taking responsibility for their waste, Bennett said it can increase their administrative work, especially for small or local companies.

"It might take a lot more manual work, and therefore a lot more time,” she said.

Some jurisdictions have exceptions for companies based on revenue thresholds. This means small companies, for example those with less than CA$2 million ($1.3 million) annually in revenue would not have to participate in EPR. However, the exception levels can be controversial and lead to accusations of unfairness.

Deciding who implements EPR

Experts said government officials should consider a few things when they draft EPR laws, such as whether to have competition between PROs and who should be the oversight body.

PRO competition can be controversial, as highlighted by Kunz’s paper. On the one hand, a monopoly can come with better control and more money for recycling services. On the other hand, competition can drive down costs, if at the expense of recycling quality.

On oversight, Ed Gugenheimer said governments can either have their oversight bodies internally or as a third party. The CEO of such a third party organization, Alberta Recycling Management Authority, Gugenheimer thinks third parties can provide a more efficient oversight function since it's their specialty, and they can recover their costs.

While some Canadian PPP programs have been around for years, others are in their infancy.

“To achieve Canada’s circular economy and recycling goals, it is estimated that approximately CA$6.5 billion ($4.5 billion) of capital investment is needed to expand existing recycling capacity to meet the growing volume of materials,” Langdon said, and called for industry, governments and stakeholders to take a strategic approach to recycling infrastructure.

“As programs mature,” he said, “there will be even more opportunity for innovation.”

This story was edited and fact-checked by Jen Zettel-Vandenhouten.