Firewise USA 101: What it is, how it works, and more

The program is a tool meant to help communities reduce the damage caused by wildfire, officials say.

We’ve heard a lot about Firewise USA during our coverage of wildfires in Minnesota. We wanted to learn more about the program, how it works, how widespread it is in Minnesota, and more.

Here’s what we found out:

What is Firewise USA?

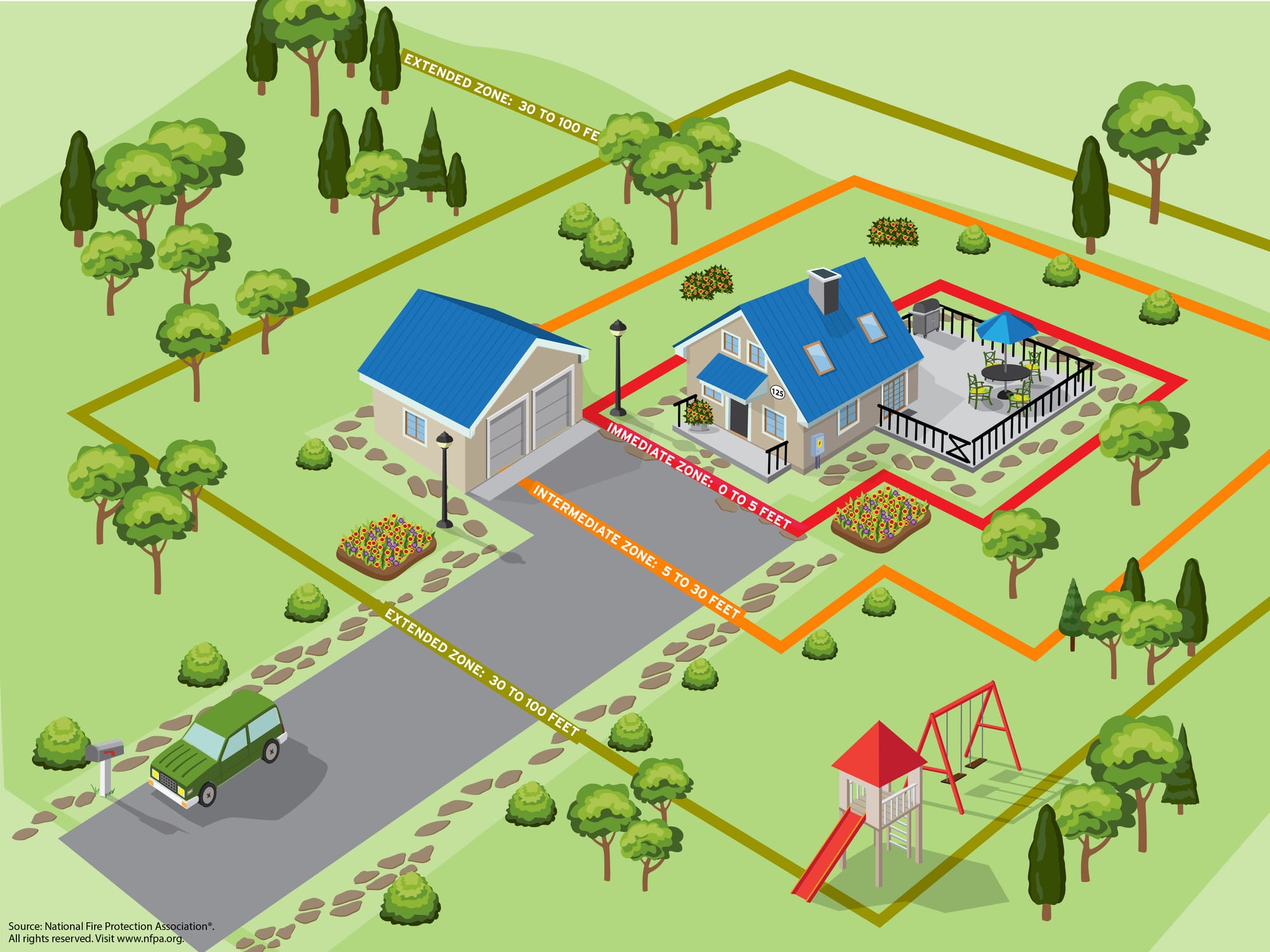

Firewise USA is a framework created by the National Fire Protection Association in 2002. It encourages homeowners to adapt their properties to hopefully reduce their risk of damage during a wildfire.

How does it work?

Firewise USA works on two main levels: with the individual property owner and with the community more broadly. Individual property owners can go through a checklist in the Firewise USA Program Toolkit. The first item on the list, for example, advises people to clear their roof, gutter, eaves, porches, and decks of material that could ignite during a fire, such as needles and leaves.

People then also work with their neighbors and other community members to become a Firewise USA Site. To become a site, community members need to form a committee, establish boundaries, register their group with the NFPA, and complete a community wildfire risk assessment. NFPA officials recommend the assessment be updated at least every five years.

“The risk assessment is the basis for creating a three-year action plan that identifies and prioritizes communitywide efforts to be taken each year,” according to the Firewise USA Program Toolkit.

From there, communities have to take the steps outlined in their assessment annually and report their work to the NFPA to be considered in good standing.

What it isn’t

Participating in Firewise USA does not make a community fireproof or guarantee that fire will never affect it, said Megan Fitzgerald-McGowan, Firewise USA program manager.

“It's a starting point, and is a way to engage those communities and get folks starting to do the work,” she said. “It's not a program saying any community is 100% fireproof or safe.”

How many communities in Minnesota participate in Firewise?

There are currently 2,452 Firewise USA sites nationwide considered in good standing, Fitzgerald-McGowan said.

A total of 16 Minnesota sites are registered with Firewise USA, according to a list on the NFPA website that Fitzgerald-McGowan verified. The communities are grouped by county below, and all fall within three Minnesota counties in the northeastern corner of the state: Cook, Lake, and St. Louis.

- Clara Lake HOA, Lutsen, Cook County

- Hungry Jack Lake Property Owners Association, Grand Marais, Cook County

- Leo Lake, Grand Marais, Cook County

- South Greenwood Lake Road Owners Association, Grand Marais, Cook County

- Tait Lake, Grand Marais, Cook County

- Voyageurs Point Homeowners, Grand Marais, Cook County

- West Bearskin Lake Property Owners Association, Grand Marais, Cook County

- Crooked/Wilson Lake, Finland, Lake County

- Ojibway Lake Summer Home Group, Ely, Lake County

- South Kawishiwi Road, Ely, Lake County

- Stony River Estates, Isabella, Lake County

- Brimson Fire Department Coverage Area, Brimson, St. Louis County

- Duluth/Alden Townships, Duluth, St. Louis County

- Eagles Nest Township, Ely, St. Louis County

- Ellsburg Township, St. Louis County

- Normanna, Duluth, St. Louis County

What are the benefits of Firewise?

Firewise USA helps people take steps to protect their biggest asset – their homes. That's what Fitzgerald-McGowan always says when asked about the benefits of the program.

“It's really meant to empower people to help themselves be safer and to kind of be a part of that bigger wildfire effort,” Fitzgerald-McGowan said.

Another benefit is community cohesion that happens when neighbors work toward becoming Firewise together.

And because Firewise USA requires a committee, Fitzgerald-McGowan said the structure can help residents pursue grants to help with their community’s efforts.

What are the limitations?

Firewise USA is a voluntary program, so people are not required to follow through in completing all the recommended actions on their risk assessments, Fitzgerald-McGowan said.

“If it's not followed up on with good encouragement to do all the things, or maybe some local ordinances that help support those efforts, it's only going to get a community so far,” she said. “It relies on those residents to be engaged.”

Another barrier for some homeowners is cost.

“Some of the recommendations, especially around improving the condition of their home, they cost money,” Fitzgerald-McGowan said. “If you have an older home with a roof that's in need of repair, that can be a lot to take on when you're trying to balance regular bills, family stuff, all those different things, so I get it. I just wish more people were able to engage before that fire happens.”

A 2018 study led by researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison pointed to one limitation of national fire prevention programs more broadly. The team found that the programs studied, which included Firewise USA, did not include information about how communities can recover after a fire.

Fitzgerald-McGowan said the NFPA is a small team that doesn’t have the bandwidth to add that information to Firewise USA at this time.

“Recovery is really important, but we at NFPA, we're a small team, and our focus is really on … before a fire, how to help protect the built environment, and we just don't have the capacity to work in that recovery space,” she said.

What does independent research say about Firewise?

Communities that were part of or closest to Firewise USA sites saw less damage to buildings during wildfires than communities that were not part of the program, according to the 2018 study introduced in the limitations section of this story.

However, some of the communities included in the study joined the program after buildings were damaged or threatened by fire.

The deeper dive:

The study, published in 2018 by the International Journal of Wildland Fire, mapped large fires that destroyed buildings in the lower 48 states from 2000-2013. To be classified as a large fire, the blaze had to burn 1,000 acres or more in the western U.S., or 500 acres or more in the eastern U.S.

The researchers noted which of those fires happened in the wildland-urban interface, or the place where human development meets undeveloped wildland.

From there, they mapped communities that participated in national fire prevention outreach programs, such as Firewise USA, Fire Learning Network, and Fire Adapted Communities, all of which exist in Minnesota.

During the time frame the researchers analyzed, there were 1,194 Firewise communities nationwide. Of those, 31% became Firewise communities after fire threatened buildings nearby.

On the flip side, 69% of the communities appeared to join proactively, before a damaging fire affected them. Among them, 13% faced blazes that threatened buildings after they joined the program, and researchers found the least amount of destruction in those communities.

In general, experts believe updating a building to code reduces fire mitigation costs. A 2019 study conducted by the National Institute of Building Sciences found that $2 is saved for every $1 spent retrofitting buildings in the wildland urban interface. The study included benefit-to-cost analysis for several types of natural disasters, including wildfire, wind, earthquakes, hurricane surge, and riverine floods.

This story was edited and fact-checked by Nora Hertel.