How Extended Producer Responsibility will work in Minnesota

Project Optimist finds out how the law aimed at reducing packaging waste could affect taxpayers, businesses, and consumers.

Minnesota has one of the highest recycling rates in the country, but officials hope to make further progress thanks to an Extended Producer Responsibility law for packaging and paper products passed in May 2024.

The state’s recycling rate has plateaued “despite ambitious goals and state financial support of local programs,” said John Gilkeson, principal planner for the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA). However, Gilkeson thinks the EPR law will bring in “new money, new fresh eyes” on Minnesota’s waste management needs and infrastructure.

“Producers feel no responsibility once [packaging waste] ends up in [your] and my shopping cart,” said Mallory Anderson, a Hennepin County policy specialist and an early advocate of the law. “And so the idea is that it extends that feeling of responsibility for them by financially holding them on the hook to make sure that that material is managed appropriately at its end of life.”

Though some materials, like products with a medical purpose, are exempt, the new EPR law puts producers on the financial hook for the materials they introduce in the state. If they make over $2 million annually in revenue, they will need to comply. Manufacturers, brand owners, importers, and distributors are also part of a hierarchy of responsibility, according to the law.

Sign up for Project Optimist's newsletter

Solution-focused news, local art, community conversations

It's free. No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

The Minnesota Chamber of Commerce initially opposed the law, in part because of Minnesota’s recycling leadership status and in part out of concern for increased costs to consumers. Since the law passed, the organization wants it to work for everyone, said Andrew Morley, the chamber's director of environmental policy. The chamber is in an “evaluation stage” as the MPCA lays the groundwork for its implementation, he said.

Representatives from Target Corp. and the Minnesota Business Partnership did not respond to Project Optimist's requests seeking comment.

Potential benefits

Some communities in greater Minnesota, like Virginia, Bemidji and Hibbing, dropped curbside recycling when the service became too costly, said Kirk Koudelka, MPCA assistant commissioner at a February 2024 legislative hearing.

Gilkeson thinks those programs will be resurrected now that the law passed, as it also promises to expand recycling opportunities across the state.

“One of the major goals of this law is to make sure that every person, as a resident in this state, has access to essentially the same program that everybody else in the state has,” Gilkeson said. “Whether you're rural, urban, small town, big city, farmer, college student – whatever you are going to have – if you're feasible for curbside, you're going to have a curbside program for collection of that material that's as convenient as waste collection.”

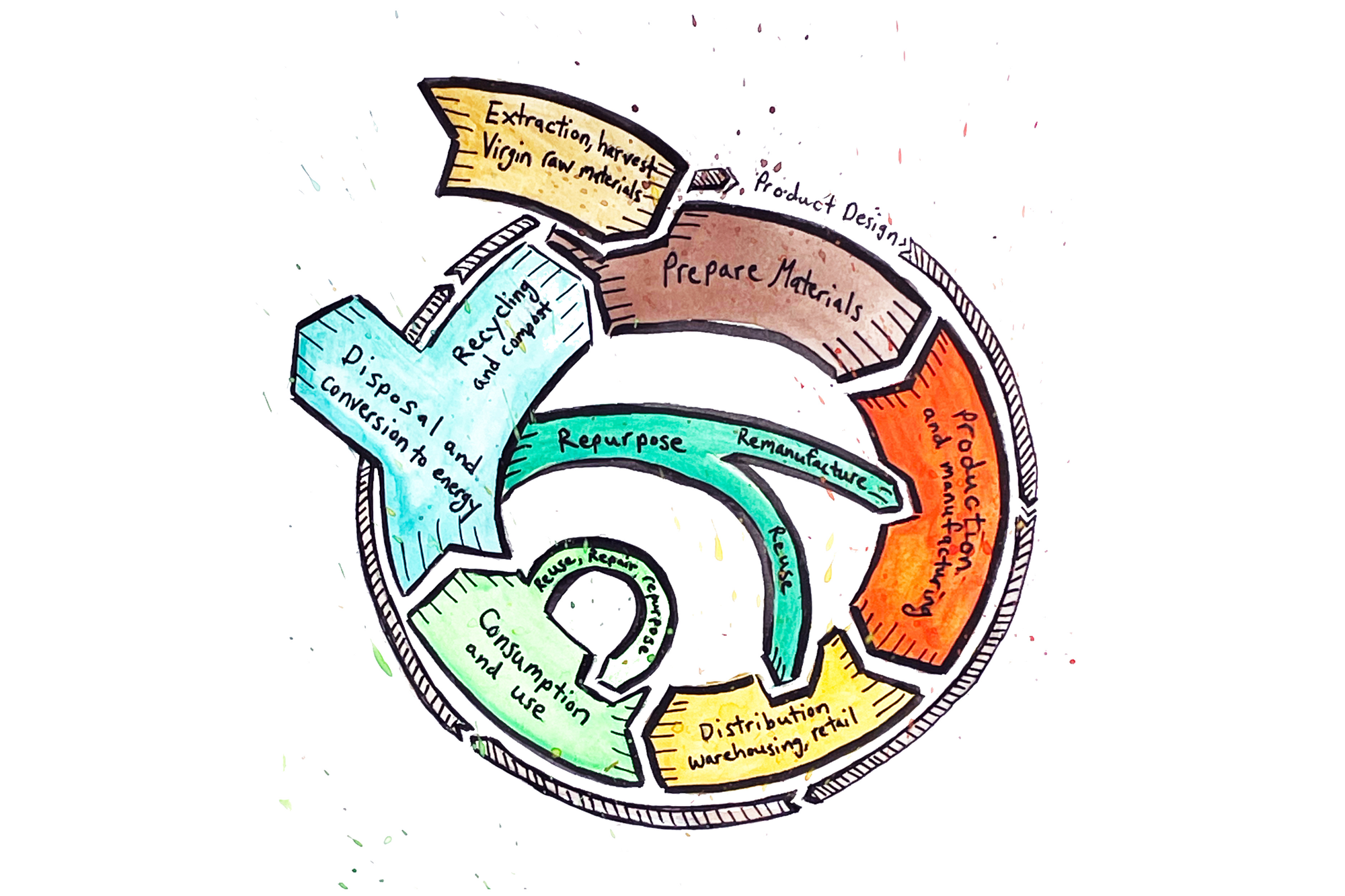

The law extends beyond recycling and says reuse systems must also expand. But that may be a big lift.

“Recycling has become easy,” Anderson said. “It’s just become what most people do. And so how do you establish systems for reuse and refill where it's just easier than the alternatives?”

Even though reuse is higher up on the waste hierarchy than recycling, Annika Bergen, a policy specialist for the MPCA, said the state’s recycling and composting systems are more developed.

“Reuse infrastructure is less established,” Bergen said in an email to Project Optimist. “There are entities focusing on expanding these efforts, but it isn’t on the scale of the strategies at the lower end of the hierarchy … I see more familiarity with recycling and organics than reuse, so it will take a lot of intention and focus to grow it across the state.”

What needs to happen first

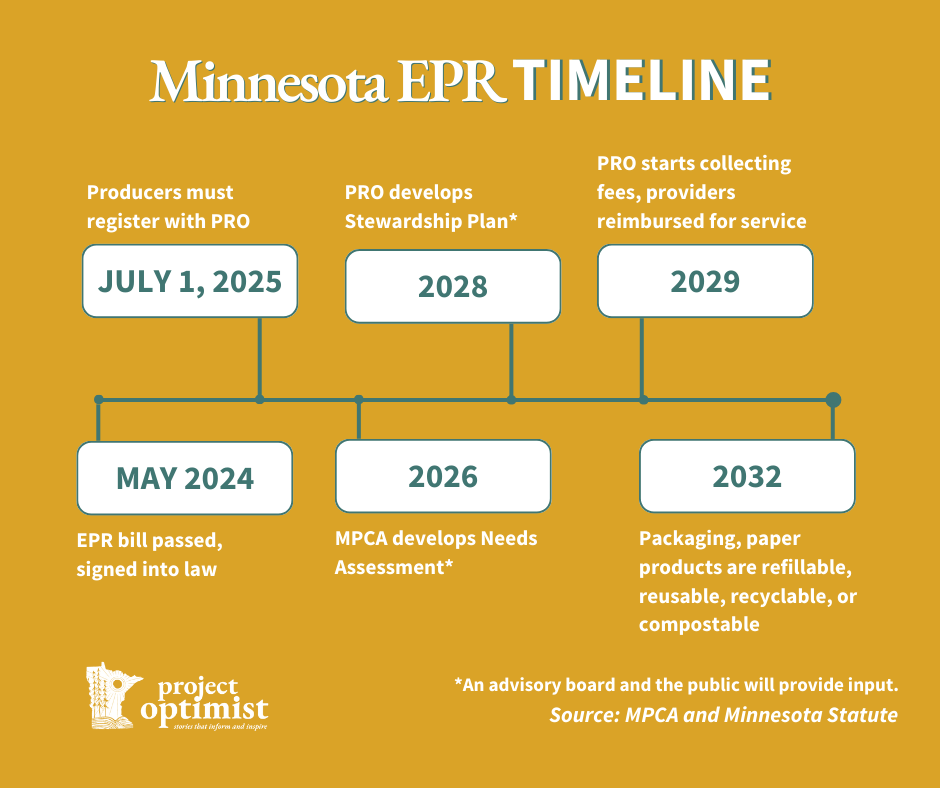

EPR in Minnesota is still a few years away. First the MPCA needs to form an advisory board and certify a Producer Responsibility Organization (PRO), as well as conduct a needs assessment.

The PRO will be a nonprofit organization formed by producers. It will collect fees from producers to fund and expand the state’s reuse, recycling, and composting programs while service providers maintain control of operations. An advisory board made up of experts from industry, recycling facilities, nonprofits, and other stakeholders will inform the law’s implementation.

Circular Action Alliance, a PRO in other EPR states, registered to be Minnesota’s in December, but the MPCA has to make it official. Only one PRO is allowed during the first stewardship plan. Then producers could form other nonprofit PROs to represent them. To ensure no gaps in service, multiple PROs would require a coordinating body to assign responsibility.

A needs assessment will take stock of what the state’s service capabilities and gaps are, and the PRO will use that to make a stewardship plan. Plans to achieve collection targets, infrastructure investments, and other efforts to advance waste reduction, recycling, and reuse will flow from the needs assessment and stewardship plan.

The MPCA will create a collection list to standardize recyclables throughout the state. It will say what materials should be collected curbside, while an alternate collection list will deal with materials that are more difficult to collect.

It’s possible subscription recycling services like Ridwell could be part of the alternate collection strategy, but the details would need to be ironed out, Bergen said.

Project OptimistJen Zettel-Vandenhouten

Project OptimistJen Zettel-Vandenhouten

Challenges

Taxpayers may see their costs go down as the PRO is required to reimburse service providers, though some providers could still charge unreimbursed costs.

What consumers will pay is unclear.

Morley said it’s inevitable that compliance costs will be passed on to consumers.

“As companies switch to alternatives for whatever that may be, it’s not going to be free. If it were, they'd have done it already, right?” Morley said. “So who knows what innovation brings in seven years, but inevitably, we do think that will be a cost passed down to the consumer.”

However, studies on the matter vary.

One study claims EPR caused no discernible price differences in Canada. A policy paper from Columbia School of Professional Studies states the maximum a producer could pass on is 0.69% of grocery spending or about $4 monthly per household. However, the Columbia paper also notes that the burden could be higher in low-income communities with food deserts, since local markets can pass down costs easier than large chains.

Project OptimistJen Zettel-Vandenhouten

Project OptimistJen Zettel-Vandenhouten

Material collection targets may be counterproductive if too ambitious, according to some stakeholders from European nations with EPR.

“I am worried that when we get to a certain point, by increasing targets we are actually going to increase environmental burden,” said a packaging producer quoted in a study of European stakeholder views. “We are just moving the burden from packaging going into landfills to collection infrastructure. This will lead to diminishing returns.”

As far as the goal to phase out what Anderson calls “trash packaging” by 2032, she said it will be difficult to meet.

“I acknowledge that you can't stand up recycling infrastructure for like a film plastic in seven years. That will be difficult,” Anderson said and pointed to exemptions in the law.

For example, the PRO could petition the MPCA for an extension to recycle plastic film if they can’t find a way to recycle it. The extension would give the PRO until 2040 to find a solution, Bergen and Gilkeson said in an email to Project Optimist.

They hope that “technical innovation and creativity will minimize these types of requests.”

This story was edited and fact-checked by Jen Zettel-Vandenhouten.