How do you get a rural doc? Launch a rural med school

The Medical College of Wisconsin launched a central Wisconsin campus 10 years ago. The effort offers lessons for University of Minnesota officials to consider as they prepare to open a new medical school campus in St. Cloud in 2025.

It takes at least six years for a new, rural medical campus to produce doctors for underserved areas.

And the need for rural doctors is growing.

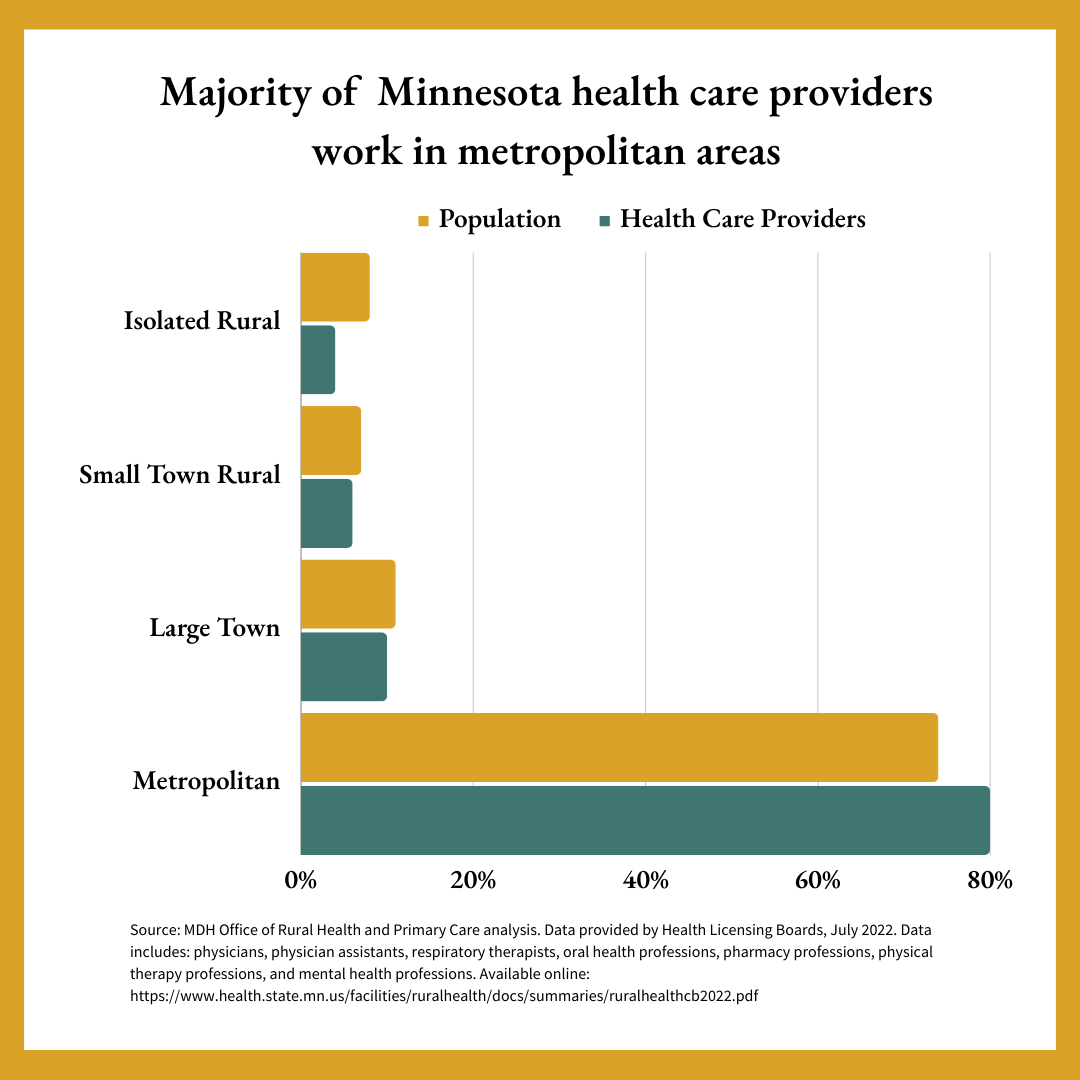

There’s a shortage of medical providers in rural parts of Minnesota, especially in primary care and mental health, according to the state Department of Health.

CentraCare and the University of Minnesota received approval in December 2023 to launch a rural medical campus in St. Cloud. It will be about eight more years before they see graduates complete their residencies.

The Medical College of Wisconsin embarked on a similar journey a decade ago. The first class of students at the Central Wisconsin campus in Wausau received their white coats and launched their formal training in 2016. So far nine of them have returned to central Wisconsin to practice and make a dent in the nationwide need for rural medical providers. Four to five more are expected to return next summer and each year after.

“Education has a long arc,” said Dr. Lisa Grill Dodson, founding dean of MCW-Central Wisconsin. “We’ve been here long enough to see our graduates returning.”

The challenges of rural

The aging of baby boomers inflicts a double blow on the health care field. Older doctors, including many who serve rural communities, will age out and retire soon. Meanwhile we see an increase in the number of aging adults and the health care needs that come with them.

Minnesota will see the number of residents 85 and older more than double in the next 35 years from 120,000 to more than 270,000. And nationally, we know that rural residents tend to be older and sicker than those in urban areas.

The physician shortage is not just a rural problem. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the problem spurring retirements and career changes tied to burnout.

Preventing burnout

Student wellness is obviously a theme at the MCW-Central Wisconsin campus. In late summer, a table overflowed with colorful vegetables from a nearby farmers market for students to take. Next to the anatomy lab, sun filled an exercise room and a lounge with a pool table, all with windows facing wooded hills.

A bulletin board headed with “Prioritize Your Health & Wellbeing,” included resources on self care, sleep hygiene, and heart health. The central hub of meeting rooms encircles a tree sculpture with art-laden branches crossing the ceiling.

Teaching self care and wellness to medical students is meant to mitigate burnout, Dodson said. “We want to start now to build that resiliency.”

Wisconsin will be short 745 primary care doctors by 2035, which aligns with the retirement of about 40% of the state’s family doctors, according to a 2018 report that’s still being cited in the health care field.

Urban and rural parts of Wisconsin have been designated "health professional shortage areas" by the federal government. A 2023 report found 41% of Wisconsin's need for primary care providers was unmet.

States and the federal government have made efforts to increase the number of health care providers. Wisconsin has a rural residency program and a loan assistance program to draw medical students to rural and other shortage areas. The University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health developed an urban program and a rural program, called the Wisconsin Academy for Rural Medicine, to increase enrollment to address shortages. And there’s the effort of the Medical College of Wisconsin to open up two satellite campuses with 50 enrollment spots.

Lessons from the field

It’s still too early to say what percent of central Wisconsin students will return to the area, said Dr. John Raymond, president and CEO of the Medical College of Wisconsin. About 28% of medical students in the state, the majority of whom study in Milwaukee and Madison, return to Wisconsin. Any local returns will be an improvement, Raymond said.

The Medical College of Wisconsin opened a Green Bay campus around the same time it opened its Wausau campus.

It would be simpler to add 50 more spots in the urban medical programs, Dodson said.

But building connections to outstate medical systems and communities is a key advantage of rural campuses. It’s those connections that help draw doctors back into smaller communities.

Over and over in interviews with Project Optimist, MCW leaders emphasized that community involvement is crucial to establishing a rural medical campus.

Community members even help select students for the program, Raymond said. “They ask: Is this someone who I’d like to be a doctor for me and my family?”

Raymond also recommends securing funds and formal commitments from partners before getting started. And, he said with a nod to Dodson, choose the right dean to launch it.

“This is not the place to start an ivory tower,” Dodson said. And she enjoys the external focus and community involvement. “It’s not a sit-at-your-desk-and-write-research-papers kind of job.”

The central Wisconsin campus is meant for students who want a different kind of training and who plan to live in nearby communities.

Medical colleges do require some population density so students get experience in pediatrics, OB/GYN, and other specialties. Those who attend the program in central Wisconsin may have to drive to Eau Claire and other communities to get that exposure. The research opportunities aren’t as rich as in, say, Milwaukee. And funding support can be another limitation.

Students who may be the first to attend college in their families may balk at the cost of medical school, Dodson said. The Green Bay and central Wisconsin campuses consolidate the traditional four years of training into a three-year curriculum, which can save the students a year of tuition, and also requires the school to find that funding elsewhere.

What’s shaping up in St. Cloud?

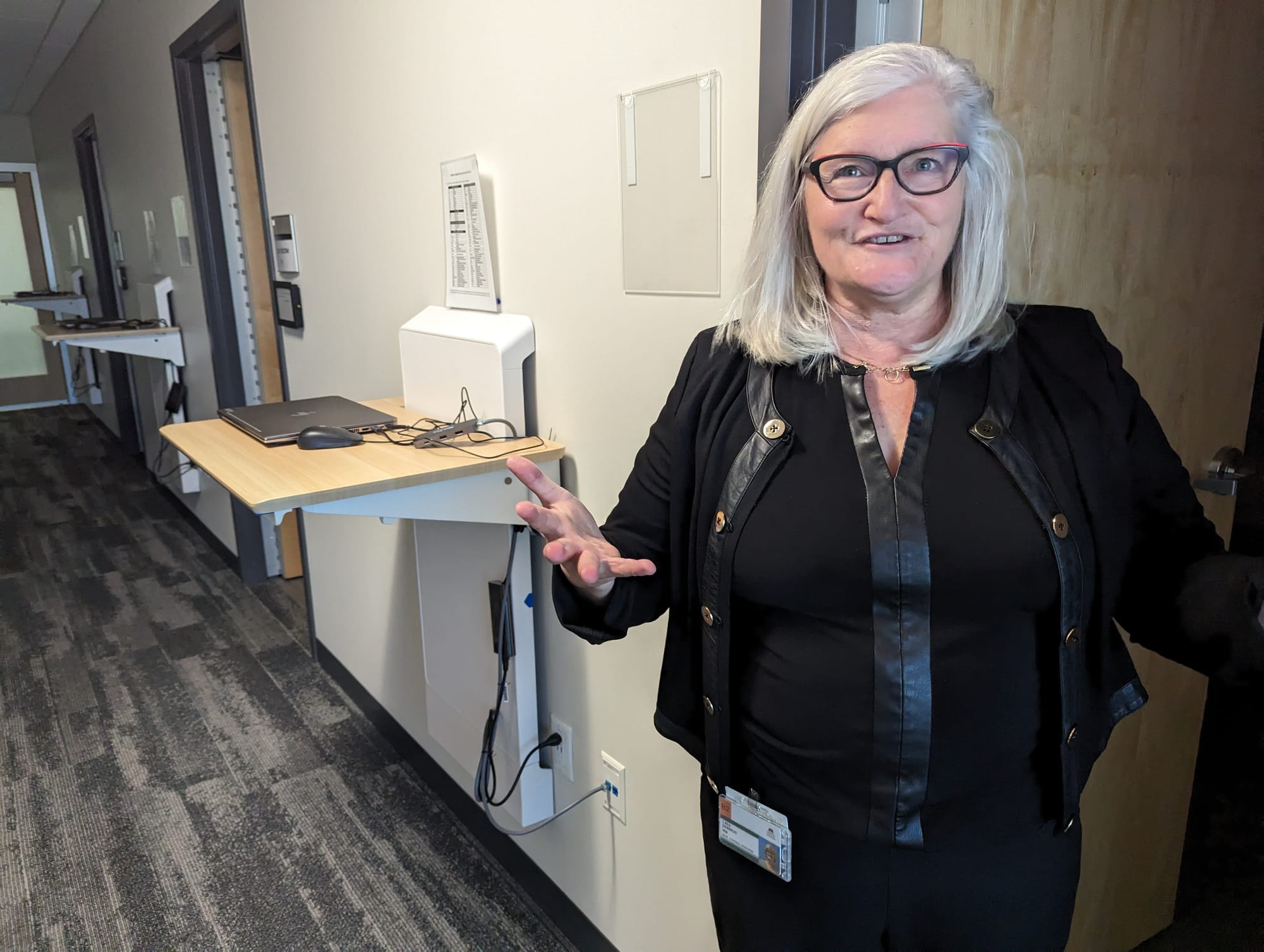

Those developing the St. Cloud campus are doing it with community and funding in mind, said Dr. Cindy Firkins Smith, vice president of medical education for CentraCare.

“This is a community project. There’s no question about it,” Firkins Smith said. “Community members have embraced it.”

Some of that support is financial. The new program has drawn $10 million in six months – a large part of its $50 million philanthropic campaign.

The University of Minnesota is also expanding its Duluth medical campus from a two-year program to a four-year program.

Medical school is more than lectures and simulations. Students shadow and work with local doctors seeing real patients. And after graduation they become residents who work in the field for three to five years.

A shortage of residencies creates a bottleneck for burgeoning doctors.

St. Cloud already has a family medicine residency program. With the growth of the medical school, the University of Minnesota and CentraCare plan to add residencies in OB/GYN, pediatrics, general surgery, behavioral health, as well as family medicine.

“The best way to make a rural doc is to start with a rural student. The data shows quite clearly,” Firkins Smith said. “Educate them locally. Train them locally. And bring them home.”

Beyond the medical school solution

Even if these rural medical campuses succeed and the number of residencies grow too, the health care field may still be short doctors or other providers. It will look very spotty across the medical landscape, Firkins Smith said.

She also expects a “halo effect” around the medical program in central Minnesota. Young people will be drawn to other health care jobs as the school develops.

“We don’t think we can solve all of the challenges of our demographic changes by just creating more physicians,” Firkins Smith said. “We’re going to rely on the team-based model which includes nurses and other health care professionals.”