Minnesota State tried a program to help students in developmental math. Now they’re expanding it

Our 10th issue explores a math program addressing disparities at St. Cloud Technical and Community College

Our 10th issue explores a math program addressing disparities at St. Cloud Technical and Community College

Our 10th newsletter is here!

Happy Wednesday! And welcome to our 10th "official" issue!

If you're new to the list, here's where you can find our first nine newsletters.

(Our earliest subscribers may remember a few editions with early updates about The Optimist in the spring. Those were direct emails and not published with our newsletter app.)

This week we're entering higher education to feature a program that takes on disparities and helps students in developmental math stay on track for their degrees or certificates.

We have reporter Clairissa Baker to thank for the in-depth story and artist Andi Lynn Arnold to thank for the original illustrations. Thanks!

Math Pathways ushers nontraditional and minority students through courses that historically slowed them down or worse

By Clairissa Baker for The Optimist

ST. CLOUD - An initiative tried at St. Cloud Technical and Community College and other schools to address disparities in math education has been expanded across the Minnesota State system.

“We just totally changed the way we offered math,” said Katie Smieja, mathematics instructor at St. Cloud Technical and Community College.

The program, which has been enacted at schools nationally, pairs a remedial math class (called a corequisite) with a college-level class to help students pass their math requirements. It’s called the Dana Center Mathematics Pathways.

Five schools in the Minnesota State system, including St. Cloud Technical and Community College and Fond du Lac Tribal and Community College, tried it successfully with grant funds in the 2020-2021 and 2021-2022 academic years.

Over the next two years, starting with courses this fall, 27 Minnesota State colleges and universities are developing, implementing and evaluating Math Pathways with corequisites. The Minnesota State system contains 33 state colleges and universities.

St. Cloud Technical and Community College began the program after faculty attended a 2019 forum on Math Pathways held by the College Board of Mathematical Sciences.

St. Cloud educators came back inspired.

Math classes are often a barrier to students completing their degrees, Smieja said. She attended that forum. She remembers thinking: “Wow, we can do this!”

Katie Smieja is a mathematics instructor at St. Cloud Technical and Community College (Courtesy of SCTCC)

The college applied for grants that the system could work with, brought in national partners and did a lot of professional development with teachers.

The result is a program that is touted as a good way to help students complete degrees or certifications on time.

The Charles A. Dana Center developed the Math Pathways model used by St. Cloud Technical and Community College and institutions across the country.

The center, based at the University of Texas at Austin, works to dismantle barriers to education. Among the center’s work is helping colleges, universities and systems create course structures that help students to finish certificates or degrees on time.

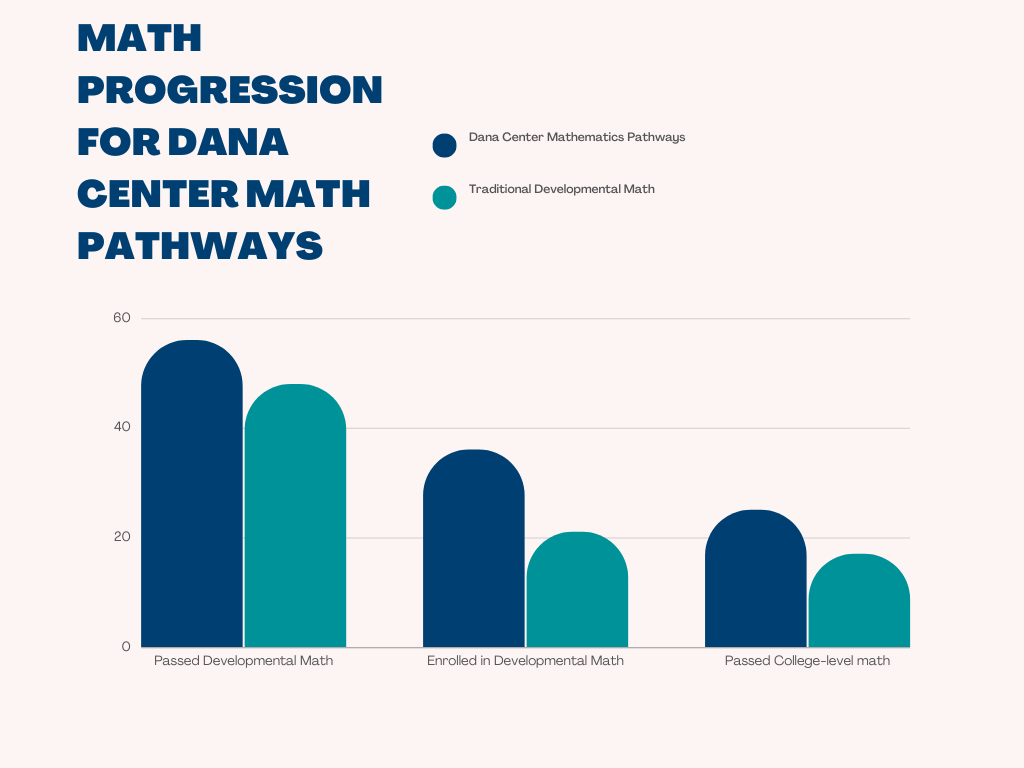

According to a research paper from the Center for the Analysis of Postsecondary Readiness, students assigned to the math program used by the Dana Center were nearly 50 percent more likely to pass college-level math than those assigned to the traditional sequences.

Filler chart - final will have source of data (Clairissa Baker for The Optimist)

St. Cloud Technical and Community College finished its fourth semester using the model this spring.

What happened before

Before Math Pathways, scores from a student’s ACT, SAT or MCA were considered for math placements. If the score was high enough, students would be placed into college-level classes, Smieja said.

If students did not take those exams, they would take a placement test and that score would determine classes that they could get into. If they were within a range of points but had a high enough GPA, students could be bumped up. The system looked at each student’s math background, Smieja said.

Students who didn’t qualify for college-level math classes had to take an extra class in order to get into the college-level classes required by their degree or certification. This could lengthen the time it took for students to complete their degrees.

Story continues below the promotion.

Promotion from The Optimist

🤓 Sign up for the newsletter!

Did someone forward you this newsletter? Did you happen upon it online? Don't miss future issues. Next we'll explore strategies to take on burnout.

Join The Optimist's mailing list!

In 2015, Minnesota State committed to redesigning developmental education. All colleges and universities worked to speed up developmental education pathways in reading, writing and mathematics through the Developmental Education Strategic Roadmap, according to Doug Anderson, spokesperson for the Minnesota State system.

According to the roadmap, which was published in February 2018, systemwide data showed that students of color, low-income and first-generation students were over-represented in developmental education. Their completion rates of those courses and of college-level English and math courses were increasing, but the gaps persisted.

White students, for example, completed developmental courses at rates 9% to 12% higher than students of color and American Indian students, according to the same document.

And with college-level math completion rates, the gap shrunk from 14% in 2009 to 11% in 2016 between white students at the universities and American Indian students and students of color.

“Addressing the opportunity gap is a key priority for Minnesota State,” according to the report.

One of the main goals in using Math Pathways is to help students of color complete college-level math at rates on par with white students, Smieja said. Another goal: “Paying attention to who we are undeserving and how we can better serve them,” she said.

Math Pathways does not work for everyone, and it has limitations including the cost of the course – which students have to pay for – and the fact it potentially takes the place of another course.

Colleges and universities in the Minnesota State system are employing the Dana Center Mathematics Pathways program in fall 2022 after a successful two-year pilot program. (Andi Lynn Arnold for The Optimist)

What happens now

The placement test and background check still happen, Smieja said. But the next steps are different now, when a student is deemed as needing support or developmental math. Before, the student would have to take one or two developmental courses first.

With Math Pathways, students take a college math class and a developmental class at the same time, and the class materials overlap.

If students are learning something in statistics tomorrow, then the co-requisite class may practice using calculators today or something else that can help with the college class.

“We are giving them the exact content and support they need when they need it,” Smieja said.

That support is the reason why Callie Carlson, a student at St. Cloud Technical and Community College, opted to do the program. Carlson decided to try it last fall after struggling with a required math class in the spring.

Carlson took her college-level math class on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. On Tuesdays and Thursdays, she participated in the corequisite class.

While the college-level class was online, Carlson said, she drove to campus for the corequisite class.

Her main class was about elements of math for elementary school teachers, which involved learning how to justify and explain concepts.

Carlson said working with the teacher and other students who also needed support helped her. And by helping her get through her main, required class, the corequisite helped keep Carlson on track for the time she wanted to spend at the college.

Carlson found out about Math Pathways after she asked her professor if she would be successful in the math class.

“I felt really anxious about taking the math class because I tried to take it in the spring semester,” Carlson said. “For me to be successful, I needed to have a little bit more help.”

Promotion from The Optimist

Support The Optimist and get some fab swag

Grab a sticker, T-shirt, notebook and more with The Optimist's hand-carved logo! All profits help fund solutions journalism & local art.

Carlson said she paid for the corequisite class, and though it did not count toward her credits, she was motivated to take the class because she was anxious about the main course.

The corequisite was interactive and involved a lot of small group and partner work, according to Carlson, and gave a sneak peak of what students would learn in the next main math class.

While the corequisite class did not assign homework, one of the downsides was that it took a place when she could have been taking another class, Carlson said. She could only sign up for a certain number of credits.

This fall, Carlson will complete her elementary program. She will transfer over to a university to finish a teaching degree following her completion at St. Cloud Technical and Community College.

Going into the corequisite class seemed scary at first because Carlson did not want to be taking math, let alone two math classes.

“It honestly really helped,” Carlson said. “I was able to get through the class with no stress and no anxiety.”

The Dana Center Mathematics Pathways programs pair a college-level course with a developmental-level requirement that covers similar topics and provides extra support to students. (Andi Lynn Arnold for The Optimist)

Focusing on student strengths and just-in-time support

Urie Treisman, a mathematics professor and executive director of the Charles A. Dana Center at University of Texas at Austin, has explored developmental math and barriers to mathematics education.

While looking at community colleges, a mentor pointed out that he only came back with reports of the wonderful teachers whose classes were successful, Treisman recalled. Maybe it would be useful to look at the state data systems to see what percentage of students actually ended up in the best classes.

“It was just a revelation,” Treisman said. “It’s the moment you want to kick yourself.”

It turned out that a small number of students who were placed in developmental education never actually reached a college-credit course.

In some systems, according to Treisman, there were hundreds of people who had completed all the requirements to be a firefighter, or get through pre-nursing or pharmacy tech programs, but they did not get the certification because of a failure in college algebra.

Some populations of students did well with stand-alone developmental classes, particularly women who had good high school educations and military veterans who didn’t have great experiences in high school but changed in the military.

“For 18 to 19-year-olds, largely it was a disaster,” Treisman said. So they began to work with corequisites instead of prerequisites, giving students “enough just-in-time support and instruction to help them pass a college course.”

“Prerequisites for everyone was an extremely bad idea,” Treisman said. Everyone organized around finding and fixing the deficits and weaknesses of students, but very few programs ever tried to figure out what the strengths were.

“Probably the biggest reason this works – where it works – is because people are focused on the strengths of the students, not just on their weaknesses,” Treisman said about the corequisite courses in Math Pathways.

The program worked at scale in Tennessee and Georgia, Treismann said, in a large system of community colleges in Texas and in institutions across the country.

“It’s a good idea that’s not all that hard to implement, but sometimes institutions will fail to do it correctly or responsibly,” Treisman said. “No one’s ever designed the perfect intervention.”

From Treisman’s perspective, Minnesota colleges have done well applying the principles of the program in a way that helps students.

But Math Pathways isn’t for everyone, and no solution will fit all students.

“When you do science, you always ask, where are you failing?” Treisman said.

Math Pathways is most likely to fail in two situations, Treisman has found. One is where the system is trying to dramatically reduce faculty and attempts to implement Math Pathways with adjunct and part-time faculty.

The other is when it becomes part of politics, Treisman said, which can always impact education.

“I’ve looked at this in almost every state. I’ve visited almost every system – it’s so clear how you can screw this up,” he said. “But it’s relatively easy to have success.”

Promotion from The Optimist

Get an ad here in exchange for sharing our content

We're soliciting trades for ad space. Simply share the newsletter with your network. We can grow together! Contact Nora: nora@theoptimist.mn

Visit the store front (it's a work in progress!)

‘A culture change’

In order to make Math Pathways work at St. Cloud Technical and Community College, the school had to change how it operates. Staff and administration had to navigate administrative processes – such as creating new courses, providing education for instructors and advisors, and updating grading policies, among other changes.

Advisors needed to be on board and understand the model, Smieja said, and those working to implement the change fought perceptions that Math Pathways meant students would take “twice the math.”

Smieja said Math Pathways is not really two math classes, it is one big class that goes deeper and helps students pull in what they need to succeed.

“It’s a culture change,” Smieja said, which involved education with colleagues about why this method is better for students.

Math Pathways needs more play at the college in St. Cloud to develop the data leaders are looking for, Smieja said. But the college has documented a comparable course success rate – that means the students who have the corequisite course with statistics are passing at the same rates as those students who aren’t in the Math Pathways program.

Students in the program would previously not have had access to the college-level class for at least a semester which, Smieja said, “is amazing.”

Final thoughts

Thanks for hanging with us until the end! I'd love to hear what you think about this piece of solutions journalism, the original art and any of the work The Optimist has published since June.

I am truly here to serve, and that means I need to know what you think of the content and whether it's reaching you at a convenient time, in a convenient way. Drop me a line: nora@theoptimist.mn.

Have a fabulous week!

♥ Nora Hertel, founder and publisher of The Optimist

Our mailing address:

P.O. Box 298

St. Michael, Minnesota 55376

Copyright © 2022 The Optimist, All rights reserved.