Not every plant takes root, but prairie interventions help with biodiversity

A St. Cloud church with a 15-acre prairie planted seedlings in 2022 that didn’t take off. Other plantings have worked. Here’s what we learned.

This story revisits a prairie restoration project featured in the first edition of the Project Optimist newsletter in 2022. We told the original story as a photo essay.

ST. CLOUD – Volunteers carried and wheeled boxes full of plants outside Bethlehem Lutheran Church in spring 2022. They planted 400 seedlings of roughly 18 different species around the restored prairie, and volunteers returned to water them all summer.

But it was a dry year, and most of the plants did not survive.

The setback did not deter Ann Gustafson-Larson, a member of the church and champion of its prairie. She organized the 2022 planting and others since that have taken root.

“Well, that was a fail. So now we learned that doesn’t work. Let’s try this fall planting. And so far, it looks like that’s worked,” Gustafson-Larson said. “I want to keep at it. Whatever we can do to improve it is going to be a positive.”

Minnesota used to have 18 million acres of prairie, and just over 1% of that remains, according to the state Department of Natural Resources.

Protected and restored prairies help support struggling pollinators and increase biodiversity, among other benefits.

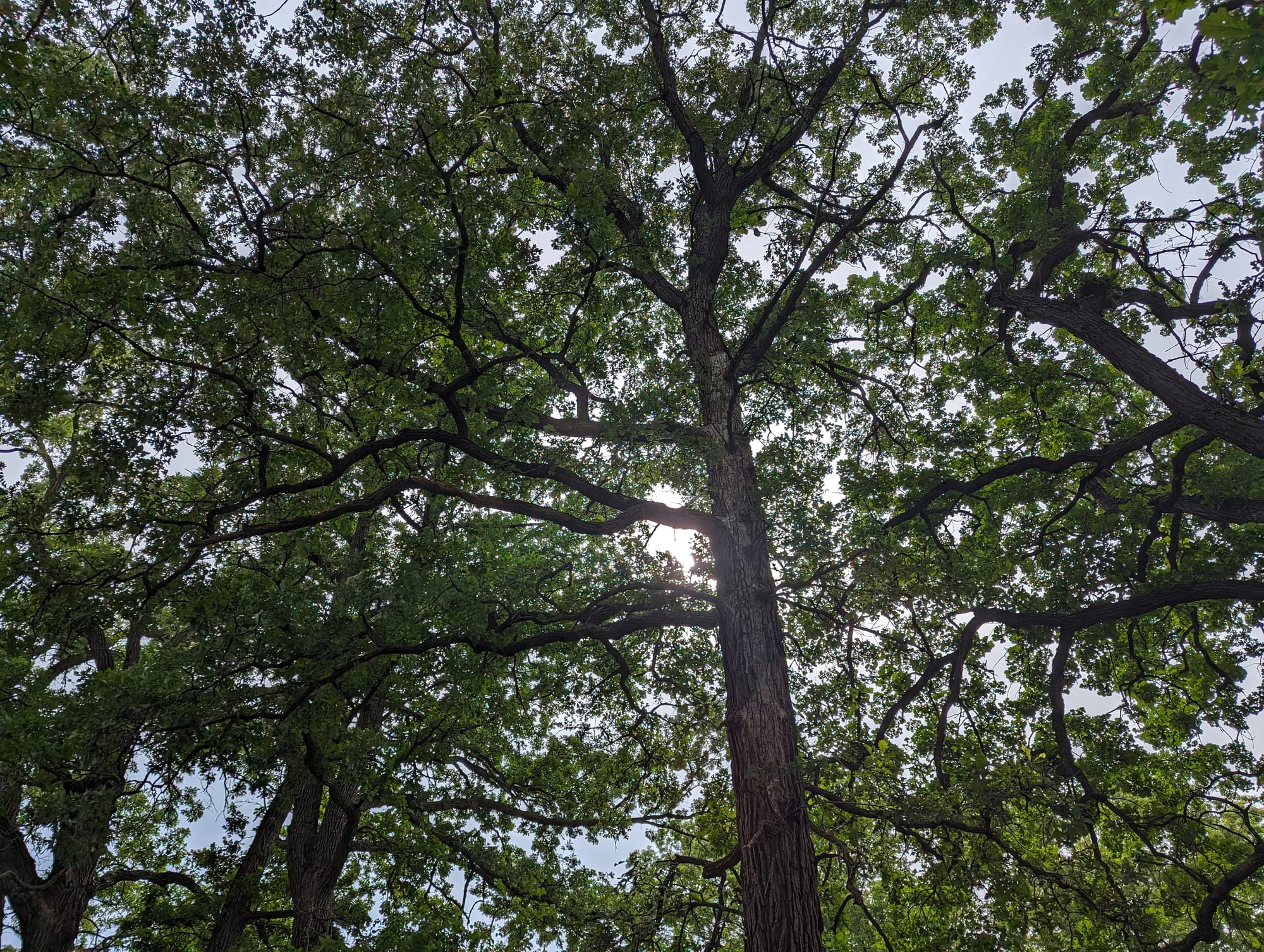

The prairie at Bethlehem Lutheran Church was restored about 25 years ago, according to Gustafson-Larson. The site was a homestead before it hosted a church. And there’s a grove of mature oak trees too, shading new ferns, violets, and other native species planted by volunteers.

One of the challenges Gustafson-Larson faces is a lack of information on how to diversify a prairie that’s already reconstructed.

People around the world have found it difficult to predict the outcome of different ecosystem restoration efforts, and there’s been a push in the last several years to identify what factors impact success, according to a 2023 article in the journal Restoration Ecology. The same article reported that more intense interventions in grasslands – from native seed scattering to controlled burns – improves the outcomes.

At the local level, you can do a survey and count plants, said Adam Hjelm, a master gardener and an education and outreach coordinator for central Minnesota watersheds. He’s helped with projects at the church prairie for the last seven or eight years.

You can also measure success in other ways.

There’s no bare soil, erosion, or dead areas, Hjelm said. “To me that’s success.”

The area experienced two years of drought conditions, and still there’s native plants, diversity among the species, and wildlife, he said.

Deer, foxes, and many species of birds pass through it. A bird walk in May brought sightings of eastern bluebirds, American goldfinches, black-capped chickadees, mallards, red-winged blackbirds, and many other species. Plus the butterflies and bees.

“If we get 20 more monarchs because we have a prairie here, I think it’s worth it,” Gustafson-Larson said.

What went wrong?

Gustafson-Larson thinks that 2022 planting didn’t work because the seedlings couldn’t take root among all the other roots in the soil.

Since then, she lays down tarps to suppress the growth of existing plants and then introduces new natives. Last year, the natives started in milk jugs and spent part of the winter, spring, and summer in containers and raised beds. They went in the ground last fall and have done well so far.

In March, volunteers planted another batch in containers that will be moved to the prairie this fall.

Children at a preschool in the church have helped support those seedlings including milkweed, lupine, and many others. The kids kept the plants watered during the drought last year.

Hjelm thinks drought hurt the 2022 effort.

“We’re at the mercy of the weather,” he said. “It’s pretty tough to control that.”

The church prairie faces some other limitations. It’s bound by Minnesota Highway 15 and housing developments. A controlled burn, which can help a prairie thrive, is not an option.

What went right?

Gustafson-Larson has found other practices and partners to manage invasive species at the prairie. One group cut down buckthorn, another killed a different invasive with targeted herbicide.

Those partnerships are another sign of success, according to Hjelm. Gustafson-Larson has assembled gardeners, naturalists, environmentalists, county agencies, a Soil and Water Conservation District, nonprofits like Wild Ones, preschool children, and birders to support the patch of prairie.

"It's a work in progress," Hjelm said. "There's a lot of help there moving forward."

On a walk through last week, the emergence of some colorful native flowers surprised Gustafson-Larson. The wet spring has helped.

“The more I come here, the more species I see,” she said.

Check it out

You can help with the fall planting. Volunteers are invited to plant seedlings at Bethlehem Lutheran Church at 9:30 a.m. on Saturday, September 7. There will be coffee at the start of the day and pizza after the planting.

The prairie is open to visitors, and there are paths mowed through it. It's located at: 4310 County Road 137, St. Cloud, Minn.

This story was fact checked by Nora Hertel with Ann Gustafson-Larson and Adam Hjelm.

Solutions Journalism Pillars

Gustafson-Larson takes on the problem of biodiversity in a restored prairie. This is a solutions journalism story, which means it includes four specific elements.

The response: Plant more native species. Kill some of the invasive species.

The evidence: Gustafson-Larson and Hjelm share qualitative observations that the 2022 planting generally did not take, but other plantings have rooted. Restoration ecologists are struggling to better predict success in grassland restoration.

The limitations: Hjelm says weather is a factor. Gustafson-Larson wants more information on improving restored prairies.

The insights: Not every intervention works. Building a coalition of supporters (including children!) increases success. Gustafson-Larson says the preschoolers watered some of the container plants every day to help them survive the drought in 2023.