'We can't ignore the reality': Minnesota community works together to prepare for wildfire

Residents of Eagles Nest Township, a small community southwest of Ely, Minn., have spent more than a decade preparing for wildfires. Here's a look at their efforts:

Ely is a small town with a big wildfire problem.

Situated entirely within Superior National Forest, the biggest national forest east of the Mississippi sits atop a 3-million-acre tinderbox. Climate change, a century of fire suppression, and the effects of a native tree insect have converged to make the town of Ely a bullseye in a forest ripe for fire.

This interactive map tells a sobering story. The darkest colors of red indicate that the forests at the edge of town are at high risk, with a 1-in-500 chance of a wildfire any given year. On the edge of town, it increases to 1-in-200.

“Those are hard odds. Ely could be another Camp Fire in the right weather and conditions,” said Hunter Bell, a Structure Protection Specialist with Northern Rockies Complex Incident Management Team 1. “I look at it and see all the firewood stacked in people’s backyards, the buildings near one another, with no defendable space or home ignition zones. It’s a real possibility.”

Directly southwest of Ely, one rural community has been preparing for the inevitability of fire for more than a decade. Eagles Nest Township is known for its expanses of beautiful old white pine, strings of sparkling lakes, and the entrance to Bear Head Lake State Park. It is also, according to people who work with wildfire, the poster child of community wildfire readiness.

“The forest has changed,” said Mike Ostlund, Eagles Nest Township’s director of emergency management. “We have spruce budworm and climate change. Everything has changed. Fires are faster. They’re burning hotter. We can’t ignore the reality. Hopefully, we can shine a light and show other communities what’s possible.”

Building the fire

Ely is a wilderness town, where seeing a bear or moose a few blocks from the town’s only grocery store would not be unusual. The boreal forest crawls up to the edges of this former mining town of 3,200, with backyards that abut hundreds of miles of roadless area.

Wildfire is no stranger here. Residents can name the fires, one by one, year by year, and how close each came to town.

The landscape is a fire-dependent ecosystem; many native tree and plant species require fire to propagate. Seed banks waiting in the soil wake up with fire, putting forth species only seen during fire conditions. Jack pine and black spruce create resin-sealed cones that readily open with fire. Blueberries – the beloved heart of Ely’s summer Blueberry Arts Festival – thrive with wildfire.

Humans are the most common cause of wildfire – and have been for millennia. In fact, scientists using tree ring and fire atlas data confirm that the traditional use of fire by the Anishinaabeg (Ojibway) played a central role in managing the forest with small, intentional fires prior to colonization.

Under those circumstances, the forest was a mosaic of young and old trees. The thick mats of vegetation and fallen branches on the forest floor burned away in low-intensity fires, opening the forest floor to sunlight.

But the 1911 Weeks Act made fire suppression the official policy of the United States government. The same law largely prohibited Native American cultural fire management. Smokey the Bear was born in 1944. A century of fire suppression has created a fire risk that is now potentially catastrophic.

Building capacity

The small township of Eagles Nest has been working on wildfire readiness for more than a decade. Momentum started when a former town supervisor suggested a backup generator for the community center — a way to keep the lights on and phones charged if people needed to come for help in an emergency.

“There’s one way in and one way out. We have 30 square miles with 23 dead-end roads that feed into just one paved road that itself is the only road in and out,” Ostlund said. “We have to consider the state parks, the Mesabi Bike Trail, and the ATV and snowmobile trails. We have a large population of seasonal residents. We have an all-volunteer fire department. It’s a lot to coordinate in an emergency.”

In Eagles Nest, residents attend free, hands-on workshops that teach safe woodpile burning practices. On community chipping days, property owners can gather woody debris at their driveway entrance to have it transformed by woodchipper machines into usable mulch. Chainsaw safety classes run regularly. Most recently, a grant paid for the creation of an atlas that details such things as community infrastructure, property ownership, road turn-around options for large emergency vehicles, and water availability.

Ostlund says the Eagles Nest’s road ambassador program holds it together. Trained volunteers stay in touch with all property owners on an assigned road, sharing information about non-emergency mitigation opportunities and serving as liaisons to the fire chief when an emergency arises.

“This is key. They are the life link to this whole thing. It’s built like an old-fashioned phone tree. We develop lists for each road or a section of road,” said Ostlund. “The population of Eagles Nest is just around 250 full-time residents. In the summer that number swells. The road ambassadors can reach people one-on-one. Everyone is connected.”

The township also formed the Eagles Nest Committee for Emergency Management (ENCEP) team, a core group of volunteers who train to meet any number of challenges.

“Those 25 people are amazing. Each person is provided with a backpack full of items that may be needed, like goggles, a helmet, wrenches for turning off utilities,” Ostlund said. “And we hold drills to see what we don’t know. Last year, an ENCEP wildfire evacuation brought dogs, cats and even a horse out of the woods.”

Challenges

Compared to many communities, Eagles Nest has a healthy roster of first responders, but in a community with an average age of nearly 64 years old, recruiting is difficult. It’s a national problem, and particularly worrisome for Minnesota. According to the U.S. Fire Administration’s National Fire Department Registry, 97% of the firefighters serving Minnesota’s 724 registered fire departments are volunteers.

“Holding a hose for 15 or 20 minutes is hard work," Ostlund said. "Training takes a lot of time and effort, and young families — however few we have in our community – just can’t commit to that level. We have to find the money for the training, and people willing to serve. These are the real issues.”

Ostlund says that about 35% of Eagles Nest residents participate in training and community programs. “Not everyone has the wherewithal to do this work. We can get grants to hire contractors to help the elderly. We can hold picnics and reach out, but some people just want to come up north and be left alone. What we lack is muscle,” Ostlund said.

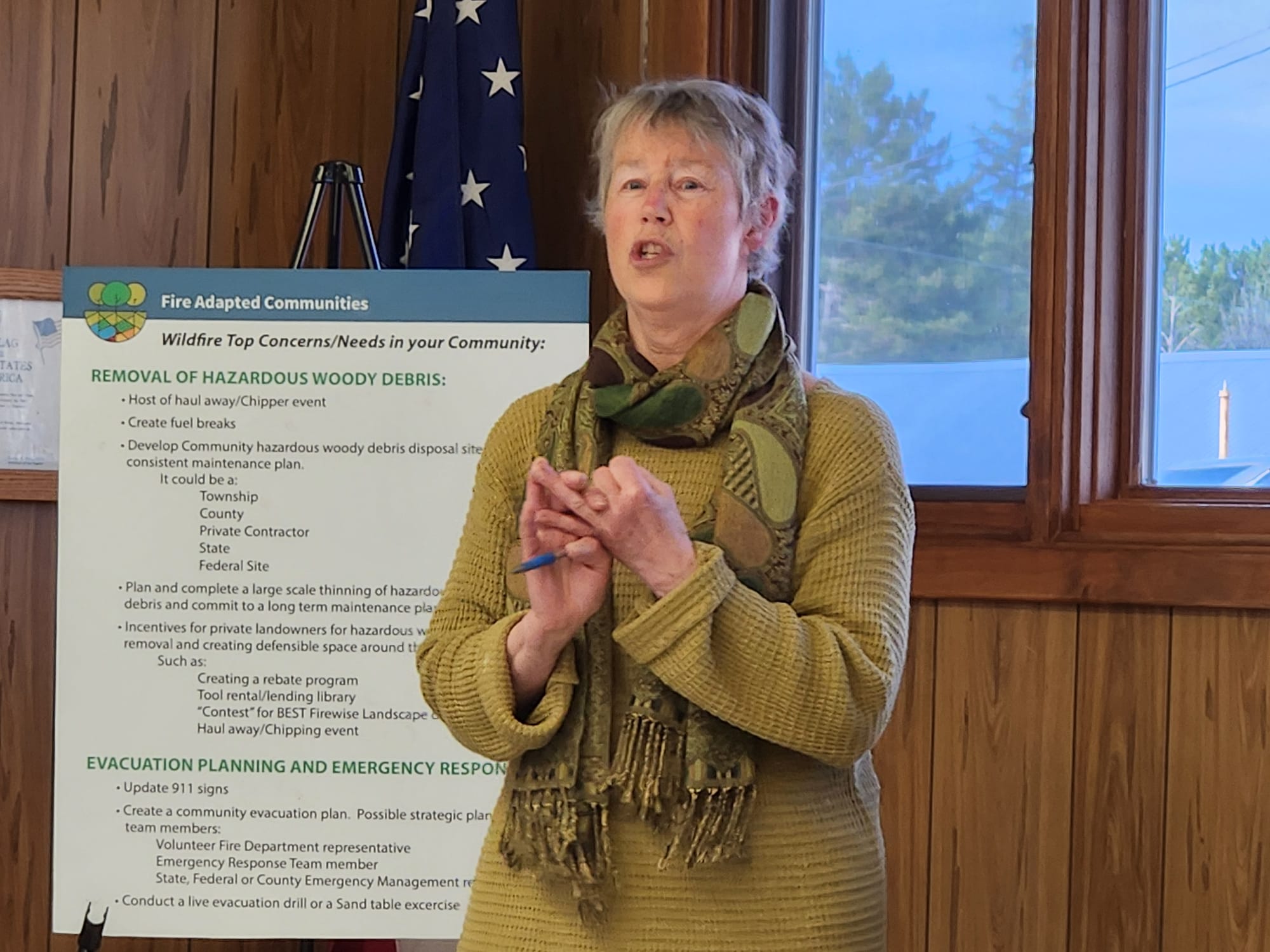

Gloria Erickson – part wildfire preparedness expert, part facilitator, and part community organizer – has supported the Eagles Nest program since the beginning. Officially, she is the Firewise Coordinator for St. Louis County. The position is supported by the St. Louis County Sheriff’s Office of Emergency Management, which receives federal funding for wildfire risk mitigation and partners with the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and U.S. Forest Service.

In a private-public partnership, Erickson is also employed by Dovetail Partners, a mission-driven nonprofit where she is the Fire Adapted Communities Project Coordinator. In this capacity, she’s able to work full-time on wildfire, and St. Louis County gains the expertise and staff of an additional partner.

Her job is huge: She is responsible for helping residents across St. Louis County’s nearly 7,000 square miles prepare their homes and communities for the risks and impacts of wildfire.

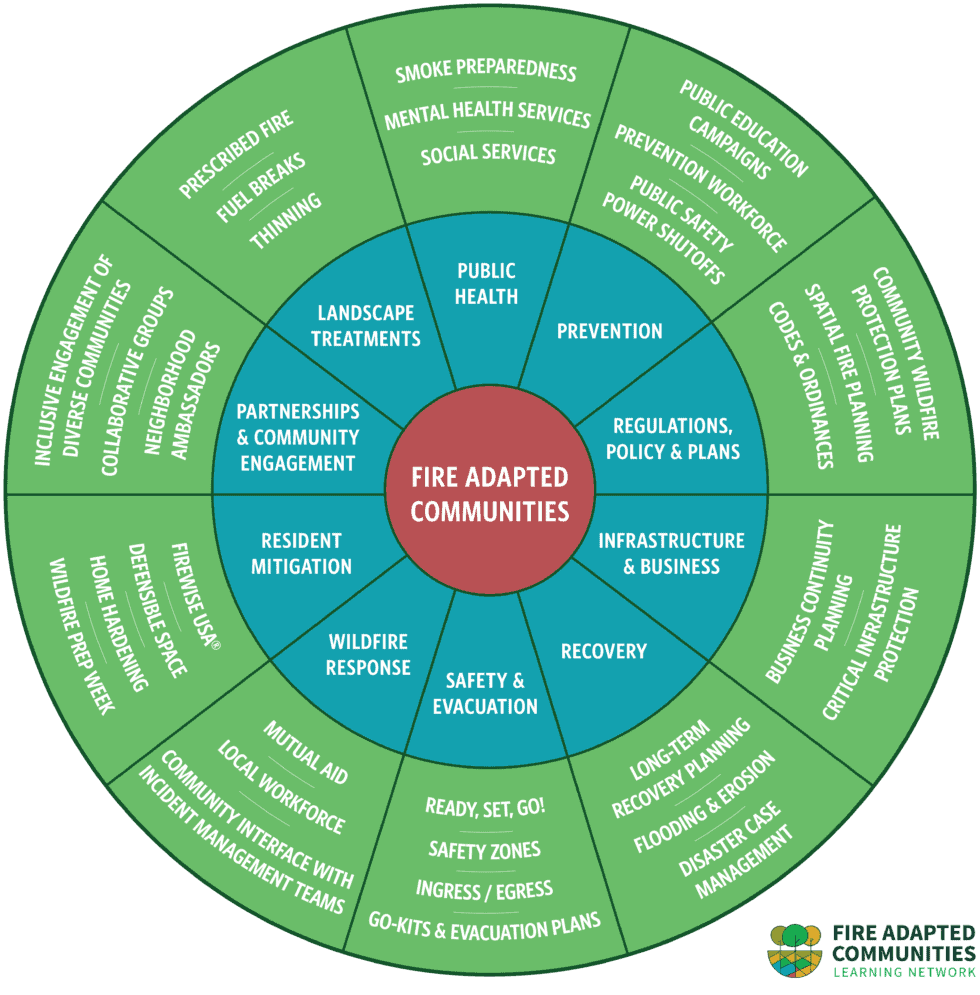

To that end, Erickson and Dovetail have been collaborating to create two support networks, connecting communities across the country where people are doing similar work. The Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network and the Minnesota-specific Arrowhead Fire Adapted Communities are designed to be a one-stop collection of resources, maps, and organizational models for community leaders.

Erickson and Dovetail are offering solutions and ideas.

“How do we create resilient, wildfire-ready communities? What needs to be done for recovery? How do we nurture volunteer groups who are asked to respond to catastrophic events – even while their own homes and families may be at risk?” Erickson asked.

“We live in a beautiful forested area, which is also an ecosystem adapted to and shaped by fire," Erickson said. "So, the question is how do we live in this place with fire? Communities like Eagles Nest show us what’s possible.”

This story was edited by Nora Hertel and Jen Zettel-Vandenhouten. It was fact-checked by Jen Zettel-Vandenhouten.