Seaplanes have patrolled northern Minnesota forests for nearly a century. They're ready for this fire season

Three planes help monitor and fight wildfires in Superior National Forest, the most at-risk national forest east of the Mississippi.

Visualize an old-fashioned floatplane. A single-engine, high-wing, propellor-driven workhorse from another time.

If it’s fire season, United States Forest Service (USFS) Chief Pilot Joel “Henny” Jungemann is buzzing the skies looking for trouble in one of those planes. Smoke, fire – anything of the sort. Twice-a-day detection flights are part of the daily routine over the 3-million-acre Superior National Forest (SNF), which includes the 1-million-acre Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW).

“It’s a 10 out of 12,” Jungemann said smiling when asked about his work flying a 1950s-era de Havilland Beaver. “These planes are fun to fly, designed for this kind of work. We have so many different missions, which keeps it interesting. And we are essentially the only pilots who get to routinely fly and land inside the BWCAW. That makes this work pretty special.”

The planes are old school, the work is challenging, and the local history is rich. For nearly 100 years, the Ely Seaplane Base has been at work in SNF. It’s older than Smokey the Bear. The forest itself was established by Theodore Roosevelt in 1909. In 1929, airplanes made their way to the Northwoods. Pilots flew the national forest skies on the lookout for fire, or transporting firefighters and equipment. In the late 1930s, the Forest Service bought its first plane.

Now the forest is home to three floatplanes, and the Beaver Program is the only USFS-staffed floatplane seabase in the country, including Alaska.

The BWCAW is the most-visited wilderness in the country. Thousands of people, on any given day, are recreating, living, or working in the national forest that surrounds it. This iconic forest, where so many go to experience nature, is alive with trails, full of paddlers on the thousands of lakes, and contains endless miles of two-lane roads that pierce the dense backcountry. It extends from Lake Superior to the east, Canada to the north, and to the west, it reaches the vast expanses of Voyageurs National Park.

The Beaver Program is just as busy with 11 distinct missions. Year-round search and rescue, medical evacuations, and body recovery missions are common. In partnership with the Minnesota DNR and tribes, there are winter moose surveys, fish stocking in remote lakes, geographical surveys, late winter tree seeding over fire scars, and aerial pest detection surveys. All year round, the Beavers are at work, serving a wide set of needs in the forest.

But during fire season, generally from April to October, pilots and planes are in fire mode – a constant state of readiness as the frontline of fire response in the Superior National Forest.

'It's a place with history'

If they’re not in the sky, the Beavers are at home at the Ely Seaplane Base, a nondescript concrete block building tucked away on the shores of Shagawa Lake. Local kids know that the public beach next to the sea base offers great views of the summer seaplane traffic. In winter, discarded Christmas trees stuck into snow drifts mark the edges of the plowed runway.

Jungemann is a retired Navy pilot who logged more than 1,000 aircraft carrier landings before working as a private pilot in Alaska, and it shows. Nothing out of place and not a speck of grease on the floor. One February day, a plane – equipped with skis – faces the hanger doors, ready to be pushed onto the ice runway if needed. The cockpit door is open, ready. The other two Beavers were being readied for the fire season.

That’s the job of mechanic and FAA inspector Tim Olsen, who is, among other things, tasked with sourcing parts. Given the fleet’s age, this can be a tricky process. On one entire wall of an adjacent room, he maintains an elaborate whiteboard tracking system, using colored pens to track his purchases and possible sources.

Upstairs, the two junior pilots are bent over screens in a room filled with charts and windows that span the wall facing the lake, which is also the runway. Before coming here, Joe Schoolcraft flew out of Moose Pass, and Jeremy Harmon out of Homer, both on the Alaskan Kenai Peninsula.

“It’s a place with history. Two of these airplanes have been here their whole lives,” Jungemann said, sharing a nearly 70-year history of photos, documents, and log books. “This is an original delivery receipt and all the maintenance records. I have pictures of the pilot delivering the plane to the dock.”

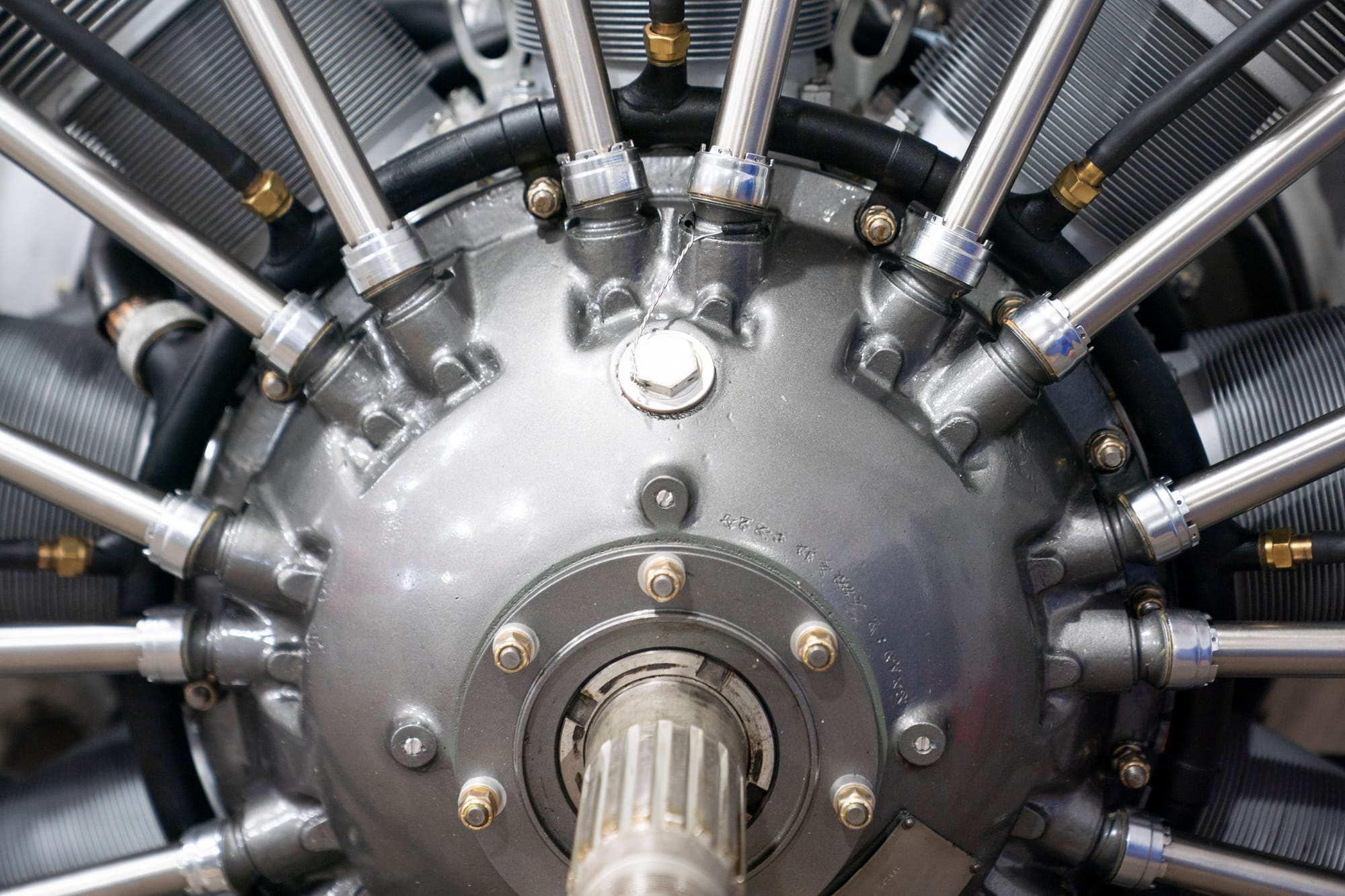

Beavers were manufactured on the heels of World War II, when airplane maker de Havilland Canada retooled from manufacturing warplanes to designing civilian bush planes. Experienced pilots suggested such things as wide cargo doors and easy-to-remove passenger seats on a plane that could land on small wilderness lakes.

These are tried and true bush planes, perfect for short takeoffs and landings, easy to convert to skis in winter and pontoons in summer, built to transport firefighters and gear. To this day, the planes are so practical and versatile that bush pilots and collectors alike keep close tabs on the nearly 1,000 Beavers still in service.

“People ask why we don’t replace them,” said Jungemann. “It’s because they’re perfect for this forest, for landing on smaller ponds, that we’re able to fulfill so many missions. People have tried to replace the Beaver, but no one has been able to do it.”

Photos of U.S. Forest Service seaplanes in action: One floatplane provides a medical evacuation at Ima Lake in July 2020; one drops water from its 125-gallon tank; another flies over Superior National Forest. (Courtesy of Joel Jungemann)

The work

A hand-fabricated deep metal hopper that clicks into place over a floor porthole for dispersing tree seeds. A set of oxygenating tanks to hold fish fingerlings that can be maneuvered into the cabin by popping out the copilot seat. These are homemade designs, crafted by previous pilots and mechanics at a time when aviation authorities were more lenient.

“That’s another reason we want to keep these Beavers in the air. No one could ever retrofit a new plane to be as effective at its job,” Jungemann said. “The modifications, to include the water-bombing tank, tree-seeder, and fish-stocking tank, were manufactured by the pilots and mechanics at the Seaplane Base, and these were approved by the FAA decades ago. That’s not happening again.”

It’s the water tanks that are the star, even amidst an impressive show of air power and pilot skill on display when the Beavers are at work. Pilots fill the tanks by dropping onto a lake, skimming while a snorkel drives water into the tank, then rising again without slowing down. Flying over treetops, they drop the water on the fire, or near it to prevent further advancement.

“We often are the only asset on the fire until ground firefighters arrive. If we have two pilots working in tandem, we can drop water every few minutes,” said Jungemann. “It’s an effective first response to wildfire.”

The 125-gallon tanks are made of discarded Korean War bombs. Each of the three Beavers has its own tank, designed specifically for that plane, numbered 1, 2, and 3. Jungemann explains the physics the previous mechanics mastered to create a snorkel that can be dropped in the water without tearing the entire contraption off its bolts.

“At first, it feels like you’re going to drive your pontoons into the water and flip when you’re filling up. You gotta drive it in there a little bit to get the water flowing,” Jungemann said. The repurposed rearview automobile mirrors attached to the wing give him a good visual of the tank. “When I see froth and water coming out of the top of the tank, I’m good to go.”

On big fires, the Beavers change missions and begin transporting crews and equipment. Loaded with hoses, axes, chainsaws, and food, the pilots transport crews. The FAA allows one canoe to be tied to one pontoon.

“That’s when we really work,” said Jungemann. “It can get pretty tiring flying behind a hot-radial engine when it is 80 to 90 degrees out, especially if we are loading and unloading the Beavers and tying and untying canoes all day. Scooping and dropping on fires can definitely wear you out.”

On high alert

Superior National Forest is a unique jewel in the national forest system. The enormous wilderness area contained within its borders. The fragile boreal forest that spills into the U.S. from Canada. The unimaginable number of lakes and streams that contain nearly half the water of all national forests combined. It’s hard to quantify and much-loved.

It’s also a huge wildfire risk. It’s the most at-risk national forest east of the Mississippi. This is no surprise to the people who live here, or the forest managers who are contending with decades of fire suppression, pest infestation, drought, and a 30-mile-long swath of downed trees left by the 1999 Boundary Waters Blowdown. The forest is dense with fuel, much of which is unreachable.

Aaron Kania is on the front lines as the USFS Kawishiwi District Ranger. He describes the Beavers as integral to the work that is done across the forest. “Yes, we have fire. But few places in the lower 48 states have this much water to work with, and we have the planes to put the water to work for us,” he said.

This winter’s unusually dry, warm weather has Kania and Jungemann on alert. In the last 20 years, the forest has experienced big fires, including the 2021 Greenwood Fire that burned 27,000 acres, and the Pagami Creek Fire of 2011, which ate through a swath of the BWCAW. Everyone is on high alert: Smoke migrating south from Canada’s forest fires during the last few summers is both hard on the body and on mental health. The presence of the Beavers on their daily flights is reassuring.

Even without wildfires, planned burns in the forest keep fire teams busy. Last year, the Beavers assisted with more than 60 prescribed burns, helping fire bosses plan an approach with aerial surveys and later providing pilot feedback to firefighters on the ground.

“Fire is a constant, a given,” said Kania. “Hours or even days before we could get firefighters into the fire, these pilots can initially size it up, get a good look at what the fire is doing, report any people or structures that are threatened ahead of the fire, and report back to the incident managers who are activating plans and teams of firefighters to respond to those threats. If needed, the Beavers can begin fighting the fire.”

With ice receding from lakes weeks ahead of normal and very little snow to melt, canoers and hikers will move in soon. Jungemann and his team are ready for a busy season, regardless of the weather.

“It’s never not interesting,” Jungemann said. “Beavers are first responders of the air. If it’s happening, we’re going to be there.”